The annual ZimVac assessment based on a national sample survey of over 10,000 households and carried out in May came out a month or two back. Unlike last year, when alarm bells were rung over a potential food security catastrophe, this year the prognosis was good. Excellent rains, including in some of the drier and usually more food insecure parts of the country, resulted in a bumper harvest.

Last year I critiqued the use of the headline figure from the assessment as potentially misleading. The same limitations of the survey apply, but the media reporting is more balanced this year (with some extreme exceptions – see comment string in an earlier blog). The survey is based on the 2012 Zimstat sampling frame and covers a large number of enumeration areas across the country, sampled proportional to population densities. Annoyingly the report still doesn't separate out communal areas and resettlement areas, and my guess is that there remains some sampling bias. More on this below. Last year fortunately the dire predictions were not borne out. In part this was because the rains came, and a green crop filled the hunger period, but also I hypothesised in an earlier blog that the production from new resettlement areas was being undercounted. I suspect this remains the case.

Anyway, I thought blog readers would like a quick summary of the report, as without an impending disaster the media has largely ignored it. You can read the powerpoint report in full, which covers all sorts ranging from nutrition to sanitation. I will concentrate on agricultural production and food security, and draw text directly from the report.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development estimates that the country will have a cereal harvest surplus of 253,174 MT in the 2014/15 consumption year from a total cereal harvest of 1,680,293MT.

Maize remained the major crop grown by most households (88%) compared to 80% for 2012/13, while groundnuts were the second most grown crop. Generally, the proportion of households growing crops increased except for cotton which showed a decline (due to the collapse in prices) and soya beans which remained unchanged.

Nationally, average household cereal (maize and small grains) production was 529.5kg. This was higher than last season (346kg). In Masvingo maize production averaged 339.7 kg and small grains 126 kg, given a total of 525.7 kg per household. Overall, average household cereal production was highest in Mashonaland West and lowest in Manicaland, and the contribution of small grains to total household cereal production was significant in Masvingo, Matabeleland North and Matabeleland South.

While improvements, these average figures are still low. And compared to the production levels from new resettlement households minute. Our studies in Masvingo, even in the poor rainfall years of between 2010 and 2012, show much higher averages (although with variations). Gareth James' studies from Mashonaland shower higher outputs still. Again in the poorer rainfall years, he recorded average outputs of maize some 12 times these average national figures for all cereals for the good rainfall year of the past season. Of course the new resettlements have proportionately fewer people and so appropriately in a national representative sample this should be reflected. But, without data broken down and without indications of variation, the ZimVac study still fails to capture this story. As I have argued before (many times!), this is important for policy, and for thinking about national food security.

The ZimVac survey showed that for the 2013/2014 agricultural season approximately 45.2% of the households benefited from the Government Input Support Scheme, which was the main source of inputs. The proportion of households accessing maize inputs through purchase remained unchanged (39%) from 2013. About 2.3% of the households accessed their maize inputs from NGOs which was a decrease from 4.0% in the 2012/13 season.

Given the higher levels of production, the national average maize price was $0.37/kg down from $0.53/ kg during the same period last year. This pattern was also reflecting at the provincial level. Matabeleland South recorded the highest maize price ($0.65/kg). This was the same pattern during the same period last year.

Livestock (cattle, sheep and goats) were in a fair to good condition when the survey took place. Grazing and water for livestock were generally adequate in most parts of the country save for the communal areas, where it was, as is normal, generally inadequate. However, the report notes, there are marginal parts of Matabeleland North and South, Midlands, Manicaland and Masvingo provinces which had inadequate grazing which may not last into the next season.

According to the report, around 60% of the households reported not owning any cattle. Mashonaland East had the highest proportion of households not owning any cattle and Matabeleland South had the least. Nationally, only 14% of the households owned more than 5 cattle with Matabeleland South and Matabeleland Matabeleland North having a higher proportion of households owning more than 5 cattle.

Like the cereal production data, these national and provincial figures are very different to what we have found (and Gareth and others) in the new resettlements. Here cattle ownership is far higher, reflecting the richer, more capitalised form of farming found. Of course the ZimVac study may suffer from under-reporting, as in many large-scale surveys with huge samples, but the contrasts are interesting – and again potentially important.

In terms of food consumption, Masvingo had the highest proportion of households consuming an acceptable diet (75%) and Matabeleland North had the lowest (54%). This showed increased local availability of foodstuffs, and improved off-farm opportunities. However, nutritional indicators remained low, including a high prevalence of stunting. As commented on before, this mismatch between food intake and nutritional indicators remains puzzling.

So, following the food balance methodology the assessment adopts (see discussion of the methodology and its limitations in an earlier blog), the report estimates that for the 2014/15 consumption year at peak (January to March next year) is projected to have 6% of rural households food insecure. This is a 76% decrease compared to the (disputed) estimate the previous consumption year.

This proportion represents about 564,599 people at peak (which may of course be people suffering deficits for only a few days), not being able to meet their annual food requirements. Their total energy deficit is estimated at an equivalent of 20,890MT of maize; actually a very small amount, and not suggesting any urgent need for food aid, given the margins of error in the estimates. Matabeleland North (9.0%), Matabeleland South (8.3%) and Mashonaland West (7.7%) were projected to have the highest proportions of food insecure households. By contrast, Manicaland (2.7%) and unusually Masvingo (3.4%) provinces were projected to have the least proportions of food insecure households.

So in sum, a good harvest results in a good food security situation. This is of course good news, and no surprise. But the report and the analysis still raise many questions. I hope that those working on food and farming in Zimbabwe can join forces and think harder about questions of sampling, the contributions of the new land reform areas to production, and the complex dynamics at the heart of the food economy that underpins food insecurity prevalence and distribution. The ZimVac annual survey is a major contribution, but with some thought and adaptation it could be contributing much more to our understanding of changing livelihoods and food economies in the post-land reform era.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Monday 29 September 2014

Beyond the ‘politics of disorder’: how bureaucratic professionalism persists in Zimbabwe’s public services

One paper on Zimbabwe at the recent ASA-UK conference that I found really interesting was the examination of the micro-politics of the Attorney General's Office by Susanne Verheul. The paper is available from the Journal of Southern African Studies. And because it won a prize, it's free to access.

The paper argues that the 'politics of disorder' frame so often used to describe Zimbabwe is inappropriate, even in that most political of offices, that of the AG. Simplistic, generalised assessments of politics, painting things in broad-brush terms as corrupt, neo-patrimonial, patronage driven or disorderly and chaotic, are too simplistic. A more fine-grained account instead shows that politics and practice operate on multiple registers. For sure many of the practices described in terms of corruption and patronage occur, but there is also a register embedded in commitments to rigour, professionalism and justice. These work in parallel, often in tension, in the day-to-day practices of the office, she argues.

In particular these tensions between registers occur within individuals. The paper offers two cases of lawyers working in the AG's office, based on interviews carried out in 2010 and 2012. Both had started work at the peak of the economic crisis in 2008. Salaries were not feasible to live on, and everyone had to seek other sources of livelihoods. Some sought these outside the office, abandoning their work; others made money from the job: through bribes and corrupt practices. These were legitimised in terms of survival, and then routinized as part of normalised behaviours. The new recruits, fresh out of law school, were horrified. This did not match their ideals of delivering professional legal support and justice for all. Yet they were torn, and accepted that for some compromises had to be made.

Of course such behaviours are not the large-scale corrupt practices that have been widely commented upon. But as small acts accrete, they create a new way of working, undermining old norms of professionalism, and in the end challenging the effectiveness of the system as a whole. Across public services, perhaps most notably with the police, this has been a consequence of those years when professional conduct was superseded by the need to survive: to feed one's family, pay school fees, treat the sick, bury the dead. Over years this has become a new normal, one that is very difficult to shift, as too many people benefit, even if the immediate need has gone.

Yet despite this, there are many who resist. And those who indulge are often torn, expressing feelings of shame and embarrassment. The two registers operate in tandem. Simply writing off public services – the courts, the police, local government, the technical line ministries – as corrupt and incompetent does not do justice to the internal, often quite personal, struggles that exist. What struck me through the period of crisis in the 2000s was how committed many of those we were working with in the Ministries of Agriculture, Lands, Environment and so on remained. They were not being paid anything near a living wage, yet came to the office. They remained committed, yet necessarily had to have outside jobs. The vets sold drugs, extension officers took payments, the lands people offered a range of services for payment. And all had other jobs, many gaining farms as a result of land reform that kept them engaged in the sector, although took them away from their formal posts.

After the stabilisation of the economy, viable salaries returned, but many of the practices persisted. But for some, like Susanne's informants in the AG's office, professional conduct, and shunning other practices was possible. This was certainly the case in the land and agriculture related technical services. Despite everything – the decimation of staff by HIV/AIDS, the flood of people out of government jobs to the private sector (including farming) or abroad, poor and often confused political leadership from the centre, and continued lack of funding, due to the fiscal challenges of government and the lack of donor support – it remains remarkable to me that Zimbabwe has such a committed group of public servants still in post. Highly trained, deeply committed, these are top professionals who continue against the odds. Compared to many others you meet in similar jobs elsewhere in the region, many (for sure not all) Zimbabwean public servants stand out, despite the poor conditions. Susanne's paper offers a nuanced and sympathetic profile of two such individuals in the AG's office, where the political spotlights shines especially brightly. But there are thousands of others elsewhere. Perhaps more in the technical ministries and in the districts further away from the political meddling who continue to uphold standards, and provide a professional service with commitment and passion. It's far from ideal, but it's not without hope.

Rebuilding the bureaucratic state, and its capacity to deliver, as part of the ongoing negotiation of a stable political settlement, must rely on such individuals. It must appeal to their commitment and professionalism, and reward this. Meeting these people in offices in far-flung parts of the country, without resources, but with ideas, understandings and a real zeal to make a difference, definitely gives me hope.

Writing off the state, and its government services, as simply a tool of a corrupt party elite is too simple, and the result of sloppy analysis. The state and its bureaucratic machinery is too complex and varied, made up of too many individuals with diverse motivations to be wholly captured in this way. A more nuanced and sophisticated analysis of politics in Zimbabwe is needed, and the sort of micro-study of a particular office offered by Susanne's paper is one way of opening up this complexity, and finding ways forward.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

The paper argues that the 'politics of disorder' frame so often used to describe Zimbabwe is inappropriate, even in that most political of offices, that of the AG. Simplistic, generalised assessments of politics, painting things in broad-brush terms as corrupt, neo-patrimonial, patronage driven or disorderly and chaotic, are too simplistic. A more fine-grained account instead shows that politics and practice operate on multiple registers. For sure many of the practices described in terms of corruption and patronage occur, but there is also a register embedded in commitments to rigour, professionalism and justice. These work in parallel, often in tension, in the day-to-day practices of the office, she argues.

In particular these tensions between registers occur within individuals. The paper offers two cases of lawyers working in the AG's office, based on interviews carried out in 2010 and 2012. Both had started work at the peak of the economic crisis in 2008. Salaries were not feasible to live on, and everyone had to seek other sources of livelihoods. Some sought these outside the office, abandoning their work; others made money from the job: through bribes and corrupt practices. These were legitimised in terms of survival, and then routinized as part of normalised behaviours. The new recruits, fresh out of law school, were horrified. This did not match their ideals of delivering professional legal support and justice for all. Yet they were torn, and accepted that for some compromises had to be made.

Of course such behaviours are not the large-scale corrupt practices that have been widely commented upon. But as small acts accrete, they create a new way of working, undermining old norms of professionalism, and in the end challenging the effectiveness of the system as a whole. Across public services, perhaps most notably with the police, this has been a consequence of those years when professional conduct was superseded by the need to survive: to feed one's family, pay school fees, treat the sick, bury the dead. Over years this has become a new normal, one that is very difficult to shift, as too many people benefit, even if the immediate need has gone.

Yet despite this, there are many who resist. And those who indulge are often torn, expressing feelings of shame and embarrassment. The two registers operate in tandem. Simply writing off public services – the courts, the police, local government, the technical line ministries – as corrupt and incompetent does not do justice to the internal, often quite personal, struggles that exist. What struck me through the period of crisis in the 2000s was how committed many of those we were working with in the Ministries of Agriculture, Lands, Environment and so on remained. They were not being paid anything near a living wage, yet came to the office. They remained committed, yet necessarily had to have outside jobs. The vets sold drugs, extension officers took payments, the lands people offered a range of services for payment. And all had other jobs, many gaining farms as a result of land reform that kept them engaged in the sector, although took them away from their formal posts.

After the stabilisation of the economy, viable salaries returned, but many of the practices persisted. But for some, like Susanne's informants in the AG's office, professional conduct, and shunning other practices was possible. This was certainly the case in the land and agriculture related technical services. Despite everything – the decimation of staff by HIV/AIDS, the flood of people out of government jobs to the private sector (including farming) or abroad, poor and often confused political leadership from the centre, and continued lack of funding, due to the fiscal challenges of government and the lack of donor support – it remains remarkable to me that Zimbabwe has such a committed group of public servants still in post. Highly trained, deeply committed, these are top professionals who continue against the odds. Compared to many others you meet in similar jobs elsewhere in the region, many (for sure not all) Zimbabwean public servants stand out, despite the poor conditions. Susanne's paper offers a nuanced and sympathetic profile of two such individuals in the AG's office, where the political spotlights shines especially brightly. But there are thousands of others elsewhere. Perhaps more in the technical ministries and in the districts further away from the political meddling who continue to uphold standards, and provide a professional service with commitment and passion. It's far from ideal, but it's not without hope.

Rebuilding the bureaucratic state, and its capacity to deliver, as part of the ongoing negotiation of a stable political settlement, must rely on such individuals. It must appeal to their commitment and professionalism, and reward this. Meeting these people in offices in far-flung parts of the country, without resources, but with ideas, understandings and a real zeal to make a difference, definitely gives me hope.

Writing off the state, and its government services, as simply a tool of a corrupt party elite is too simple, and the result of sloppy analysis. The state and its bureaucratic machinery is too complex and varied, made up of too many individuals with diverse motivations to be wholly captured in this way. A more nuanced and sophisticated analysis of politics in Zimbabwe is needed, and the sort of micro-study of a particular office offered by Susanne's paper is one way of opening up this complexity, and finding ways forward.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Tuesday 23 September 2014

Connecting development actors in Ethiopia: linking climate change, nutrition and gender

Over the past few days, ordinary people from around the globe have taken to the streets to show their concern at the lack of political will to deal with climate change. At today’s special UN summit in New York, the world will be watching how our leaders respond.

One of the issues likely to be on the agenda is food security. As demonstrated in the latest IPCC report, climate change is having an impact on already worrying levels of hunger and undernutrition in the world. This evidence has reinforced the importance of agriculture becoming more climate smart in order to: increase food security, adapt to build resilience, and reduce agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation).

This blog post examines IDS’ recent work in Ethiopia, touching upon how nutritionists, agriculturalists, gender, environmental and climate change professionals are starting to talk to one another and respond to the need for climate smart agriculture.

What the numbers tell us

Agriculture accounts for over 46 percent of Ethiopian GDP (2006), and is highly sensitive to seasonal variations in temperature and moisture. Worryingly, the World Bank has calculated that climate change may reduce Ethiopia’s GDP by up to 10 percent by 2045. In addition, the country has one of the highest rates of malnutrition globally. In 2011, 44 percent of children under five years old were stunted (meaning their height was far lower than the average for their age), which is 14 percent higher than the average for developing countries.

The Ethiopian government has exciting ambitions: to achieve middle-income status by 2025 in a carbon neutral way. The National Nutrition Plan and the Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy have outlined ways to meet this aspiration. However, when we discussed these plans with various actors in Ethiopia, it seemed that the ongoing work is still in siloes- people are working hard to support their national development but not linking up or learning from other sectors.

What has IDS been trying to do?

The Irish Aid funded project has given the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) team the opportunity to build a partnership with the Ethiopian Public Health Institution (EPHI), to bring together and connect some of the key actors; support them in building their capacity to share knowledge ;and examine the thematic links that can further build on their research. In

2012, we brought together people working across these three themes and asked: Who plays a role in sharing nutrition and climate change [adaptation] information in Ethiopia?

We were able to explore what knowledge sharing techniques and tools could be used to enhance intersectoral sharing; and developed commitment statements of how participants were going to take a small action to integrate their implement their learning.

Taking individual action

It has been exciting (and challenging) to see these commitments grow over the year. Not all have become a reality; lack of time, institutional and collegial support, and changes in staff have all played a role, but some inspiring activities have also emerged. In August, participants were invited to share their success and highlight challenges, and exchange advice and learning.

It has been exciting (and challenging) to see these commitments grow over the year. Not all have become a reality; lack of time, institutional and collegial support, and changes in staff have all played a role, but some inspiring activities have also emerged. In August, participants were invited to share their success and highlight challenges, and exchange advice and learning.

For example, Nuriya Yusuf, Gender Directorate at EPHI, committed to conduct an institutional training programme on Gender, Nutrition and Climate Change for EPHI employees. She brought together over 50 employees, both men and women for free, face-to-face training on the impacts of nutritional issues on their family lives. With backing from senior management she plans to continue the project and has been invited to share her learning with other institutions.

Another participant, DFID Ethiopia Nutrition Advisor Berhanu Hailegiorgis, was keen to strengthen internal sharing of relevant cross-cutting knowledge between teams and advisors. Berhanu has now been invited to present on the interdisciplinary links at the next internal retreat to further drive understanding and momentum on this agenda for DFID in Ethiopia.

Lessons learned for the future

There was a general consensus that issues need to be better linked, but there are also a lot of research gaps. Some of these include:

By Fatema Rajabali

One of the issues likely to be on the agenda is food security. As demonstrated in the latest IPCC report, climate change is having an impact on already worrying levels of hunger and undernutrition in the world. This evidence has reinforced the importance of agriculture becoming more climate smart in order to: increase food security, adapt to build resilience, and reduce agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation).

This blog post examines IDS’ recent work in Ethiopia, touching upon how nutritionists, agriculturalists, gender, environmental and climate change professionals are starting to talk to one another and respond to the need for climate smart agriculture.

What the numbers tell us

Agriculture accounts for over 46 percent of Ethiopian GDP (2006), and is highly sensitive to seasonal variations in temperature and moisture. Worryingly, the World Bank has calculated that climate change may reduce Ethiopia’s GDP by up to 10 percent by 2045. In addition, the country has one of the highest rates of malnutrition globally. In 2011, 44 percent of children under five years old were stunted (meaning their height was far lower than the average for their age), which is 14 percent higher than the average for developing countries.

The Ethiopian government has exciting ambitions: to achieve middle-income status by 2025 in a carbon neutral way. The National Nutrition Plan and the Climate Resilient Green Economy Strategy have outlined ways to meet this aspiration. However, when we discussed these plans with various actors in Ethiopia, it seemed that the ongoing work is still in siloes- people are working hard to support their national development but not linking up or learning from other sectors.

What has IDS been trying to do?

The Irish Aid funded project has given the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) team the opportunity to build a partnership with the Ethiopian Public Health Institution (EPHI), to bring together and connect some of the key actors; support them in building their capacity to share knowledge ;and examine the thematic links that can further build on their research. In

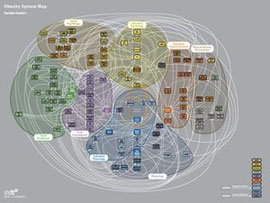

2012, we brought together people working across these three themes and asked: Who plays a role in sharing nutrition and climate change [adaptation] information in Ethiopia?

|

| Figure 1: Ethiopian Map: A complex network in Ethiopia |

Taking individual action

It has been exciting (and challenging) to see these commitments grow over the year. Not all have become a reality; lack of time, institutional and collegial support, and changes in staff have all played a role, but some inspiring activities have also emerged. In August, participants were invited to share their success and highlight challenges, and exchange advice and learning.

It has been exciting (and challenging) to see these commitments grow over the year. Not all have become a reality; lack of time, institutional and collegial support, and changes in staff have all played a role, but some inspiring activities have also emerged. In August, participants were invited to share their success and highlight challenges, and exchange advice and learning.

For example, Nuriya Yusuf, Gender Directorate at EPHI, committed to conduct an institutional training programme on Gender, Nutrition and Climate Change for EPHI employees. She brought together over 50 employees, both men and women for free, face-to-face training on the impacts of nutritional issues on their family lives. With backing from senior management she plans to continue the project and has been invited to share her learning with other institutions.

Another participant, DFID Ethiopia Nutrition Advisor Berhanu Hailegiorgis, was keen to strengthen internal sharing of relevant cross-cutting knowledge between teams and advisors. Berhanu has now been invited to present on the interdisciplinary links at the next internal retreat to further drive understanding and momentum on this agenda for DFID in Ethiopia.

Lessons learned for the future

There was a general consensus that issues need to be better linked, but there are also a lot of research gaps. Some of these include:

- What kind of adaptive capacities are needed for better nutrition for women and children?

- Links between climate change, nutrition and gender across different institutions in Ethiopia and ideas on how can these areas be better integrated

- Drought resistant mechanisms and nutrition

By Fatema Rajabali

Friday 19 September 2014

16 September 2014: China and Brazil in African Agriculture - news roundup

This news roundup has been collected on behalf of the China and Brazil in African Agriculture (CBAA) project.

This news roundup has been collected on behalf of the China and Brazil in African Agriculture (CBAA) project. For regular updates from the project, sign up to the CBAA newsletter.

Book Review of ‘Agricultural Development and Food Security in Africa’

A book review by Lídia Cabral has been published in the Journal of Agrarian Change. It covers the book ‘Agricultural Development and Food Security in Africa: The Impact of Chinese, Indian and Brazilian Investments, edited by Fantu Cheru and Renu Modi. London: Zed Books. 2013’

(Journal of Agrarian Change)

Brazil’s strategy in Africa: business, security and defence

CEBRI, a Brazilian think-tank, has released a Special Edition discussing Brazilian strategy in Africa. This Edition is composed of five articles. Two articles analyse the role of Brazilian companies, while the others look at security and defence. (CEBRI – in Portuguese)

China formalises foreign aid law – and consults public

In April, 2014, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) published a draft of its ‘Measures for the Administration of Foreign Aid’. Marina Rudyak is a PhD student from the University of Heidelberg and has done a translation of the document with a short blog analysing the draft: “Consisting of 51 articles, the Measures are the first comprehensive legal document with the character of a law to regulate Chinese government's foreign aid. Interestingly, following a practice already applied in preparation to the last Five Year Plan, MOFCOM was seeking comments and suggestions from the Chinese public.”

(China Aid Blog)

‘Brazil risks its image in Africa with neo-colonial practices’

This article looks at how Brazilian multinationals have become the main actors within Brazil-Africa relations. It argues that despite Brazilian government narratives of justice and equality, Brazil’s multinationals are now driving an extractive relationship, reflected by the fact that in 2012, 90% of Brazil’s imports from Africa were natural resources. He draws similarities with China, but argues that while China is trying to change this image of neo-colonialism, the debate in Brazil is paralysed.

(Folha de S. Paulo – in Portuguese)

Brazil-North African plans

The Arab Brazilian Chamber of Commerce plans to send a trend mission to North Africa in the first half of 2015. The trip would cover Egypt, Algeria and Morocco. The CEO and government relations manager of the Chamber has also recently held meetings with representatives from the FAO and EMBRAPA regarding Brazilian projects with small-scale farmers and the Bolsa Familia.

(Brazil Arab News Agency)

Small-scale African farmers under threat from climate change

A new report by AGRA shows that many small-scale farmers across Africa face threat from failed seasons this year, putting many communities’ and countries’ food security at risk. The report suggests that such small-scale food producers face a risk of being overwhelmed by the pace and severity of climate change.

(BBC)

Zimbabwean economist criticises Sino-Zim relations

A Harare-based economist and columnist, Vince Musewe, was interviewed for the China-Africa podcast. In it he says that “Beijing is 'bleeding Zimbabwe dry' through loans and Musewe says enough is enough. He is calling on Robert Mugabe's government to come clean and reveal the secret deals between the two governments, otherwise Musewe warns Zimbabwe will only sink further in to economic desperation.”

(China-Africa podcast)

Africa’s Regional Economic Communities and China

A new report on Chinese engagement with African Regional Economic Communities concludes that the regional communities should develop stronger frameworks to attract investment. It highlights the role of regional banks in facilitating engagements with China. The report, by the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University, focuses on the ECOWAS, SADC and EAC regions of Africa.

(Centre for Chinese Studies)

A book review by Lídia Cabral has been published in the Journal of Agrarian Change. It covers the book ‘Agricultural Development and Food Security in Africa: The Impact of Chinese, Indian and Brazilian Investments, edited by Fantu Cheru and Renu Modi. London: Zed Books. 2013’

(Journal of Agrarian Change)

Brazil’s strategy in Africa: business, security and defence

CEBRI, a Brazilian think-tank, has released a Special Edition discussing Brazilian strategy in Africa. This Edition is composed of five articles. Two articles analyse the role of Brazilian companies, while the others look at security and defence. (CEBRI – in Portuguese)

China formalises foreign aid law – and consults public

In April, 2014, China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) published a draft of its ‘Measures for the Administration of Foreign Aid’. Marina Rudyak is a PhD student from the University of Heidelberg and has done a translation of the document with a short blog analysing the draft: “Consisting of 51 articles, the Measures are the first comprehensive legal document with the character of a law to regulate Chinese government's foreign aid. Interestingly, following a practice already applied in preparation to the last Five Year Plan, MOFCOM was seeking comments and suggestions from the Chinese public.”

(China Aid Blog)

‘Brazil risks its image in Africa with neo-colonial practices’

This article looks at how Brazilian multinationals have become the main actors within Brazil-Africa relations. It argues that despite Brazilian government narratives of justice and equality, Brazil’s multinationals are now driving an extractive relationship, reflected by the fact that in 2012, 90% of Brazil’s imports from Africa were natural resources. He draws similarities with China, but argues that while China is trying to change this image of neo-colonialism, the debate in Brazil is paralysed.

(Folha de S. Paulo – in Portuguese)

Brazil-North African plans

The Arab Brazilian Chamber of Commerce plans to send a trend mission to North Africa in the first half of 2015. The trip would cover Egypt, Algeria and Morocco. The CEO and government relations manager of the Chamber has also recently held meetings with representatives from the FAO and EMBRAPA regarding Brazilian projects with small-scale farmers and the Bolsa Familia.

(Brazil Arab News Agency)

Small-scale African farmers under threat from climate change

A new report by AGRA shows that many small-scale farmers across Africa face threat from failed seasons this year, putting many communities’ and countries’ food security at risk. The report suggests that such small-scale food producers face a risk of being overwhelmed by the pace and severity of climate change.

(BBC)

Zimbabwean economist criticises Sino-Zim relations

A Harare-based economist and columnist, Vince Musewe, was interviewed for the China-Africa podcast. In it he says that “Beijing is 'bleeding Zimbabwe dry' through loans and Musewe says enough is enough. He is calling on Robert Mugabe's government to come clean and reveal the secret deals between the two governments, otherwise Musewe warns Zimbabwe will only sink further in to economic desperation.”

(China-Africa podcast)

Africa’s Regional Economic Communities and China

A new report on Chinese engagement with African Regional Economic Communities concludes that the regional communities should develop stronger frameworks to attract investment. It highlights the role of regional banks in facilitating engagements with China. The report, by the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University, focuses on the ECOWAS, SADC and EAC regions of Africa.

(Centre for Chinese Studies)

By Henry Tugendhat

Monday 15 September 2014

New research on land reform in Zimbabwe

As mentioned last week, the University of Sussex hosted the major biennial UK African Studies Association conference. Around 600 delegates were registered, and there was a real buzz, with panels on every conceivable topic from every corner of the continent. Quite a few papers reported on new work from Zimbabwe, and land and politics was a recurrent theme. In the end we had a single panel of three papers (as several panellists had to drop out at the last minute). It was a fascinating session to a standing-room-only audience.

The three panellists all reported on new research in the now not-so-new resettlements, representing different geographic areas, and diverse methodologies. All looked at how new livelihoods are being carved out following land reform in A1 sites. This included in-depth reflections on the relationships between farmers and farmworkers, a quantitative assessment of production outcomes across sites compared to communal and old resettlement areas, and an analysis of how farm and off-farm livelihood opportunities are combined in a mining area.

The session kicked off with an excellent paper by Leila Sinclair-Bright who discussed the changing social relations between 'new farmers' on an A1 resettlement area in Mazowe and farmworkers. Through a deep, focused ethnographic approach she looked at changing notions of 'belonging', and the way livelihoods are negotiated. A case of a chief's court dispute over land highlighted many of the dynamics. For, while the farmworkers were accepted as part of the farm community, and even incorporated into the cultural fabric of life through their as 'sahwira' at burials, when a group tried to claim formally the land that they had been cultivating this was rejected by the A1 farmers.

'Belonging' had its limits, and the new farmers tried to circumscribe this, arguing that as 'foreigners' (many had Malawian origins several generations back), their role was not as land owners but labourers. That the farmworkers had been bargaining hard on wages and opting for alternate livelihoods had played into this tension. Certainly the emerging forms of 'belonging' differ dramatically from that described by Blair Rutherford in the pre-land reform era, but the cultural politics of farmworker-farmer relations are as live as ever, often flaring up into disputes of this sort.

Leila's paper highlighted the value of really in-depth analysis of cases to uncover the textured dynamics of change on the farms. We have been subjected to far too much simplistic analysis, often based on spurious statistics, on farmworkers, but this sort of work really provides a much-needed qualitative insight that is immensely revealing. As the new social, political and economic relations are negotiated on the new farms, new bargains and accommodations will be struck, and this will require innovations in institutional and cultural practices; sometimes drawing on traditional norms, but in other cases requiring new deals to be struck.

Taking a very different approach, Gareth James offered an overview of some of his impressive survey work across three districts in Mashonaland/Manicaland, involving a sample of over 600. This involved a large sample extending the classic work by Bill Kinsey and colleagues that tracked the fortunes of 'old resettlement' area farmers, comparing these to their neighbours in the communal areas (see our Masvingo work on this, in a recent blog series). Gareth has developed a sample in A1 farming areas, and looked at a range of factors. This presentation focused on 'outcomes' and in a series of graphs he showed how the A1 farmers on average outperformed both the old resettlement area and communal area farmers across a range of criteria. As younger, more educated, more capitalised farmers, they had higher outputs and yields of major crops (maize, cotton, tobacco), applied more inputs and achieved higher incomes. He offered a listing of the constraints faced too, which included a familiar array focused on the challenges of accessing farming inputs and labour. For those of us who primarily work in the drier south of the country, the production statistics were impressive. Across the two seasons studied (both of which were not good seasons), the A1 farmers achieved an average output of around 6 tonnes of maize. Taking the standard figure of annual consumption requirements of 1 tonne per family, this means around 5 tonnes could be sold, and contribute to a dynamic of investment and accumulation that Gareth described. This was of course added to by the often impressive outputs of tobacco. Averages of course only tell one part of the story, and as he pointed out there is much variation. As we have seen in Masvingo, these dynamics create new patterns of differentiation and associated class formation in the new resettlements, with major consequences for agrarian social relations and longer term change. There was insufficient time in the presentation to explore these issues, but the results are tantalising, and the overall output statistics impressive. Of course there are qualifications, and some of these were discussed. Is this a temporary boom, based on the 'mining' of the soil? Will the success attract more and more people to area, and so undermine per capita success as land and outputs are shared among more and more? Did the new settlers manage to outcompete their neighbours through preferential access to inputs, offered through political patronage? All of these factors are important, but do not undermine the overall story of a production boom, with major opportunities for accumulation in the new resettlements.

The final paper by Grasian Mkodzongi reflected on his work in Mhondoro Ngezi in Midlands Province. Here A1 and A2 resettlement areas are in close proximity to the major Zimplats mining complex. Grasian's paper concentrated on the relationships between farming and mining, as mediated through labour contracts, business opportunities and political connections. In addition to the large-scale mine there are many other smaller mining operations, for gold and other minerals that provide opportunities for others. The paper focused on the social and political negotiation of the farming-mining relationship, based on a number of cases. New farmers are able to insert themselves into the economic activity associated with Zimplats, supplying inputs (such as silica found on their farms) as well as profiting from upstream aspects of the value chain. Farmers have used the politically-charged debate around 'indigenisation' to their advantage, manipulating the rhetoric and demanding economic benefits. This sets up new political and economic relationships between the farms and the mine that are played out through local political dramas. The story is immensely complex and fast evolving, but it offers an insight into how, at the local level, new economic relations with capital are being negotiated, and how a very particular political dynamics and discourses influence this. Contrary to analyses that offer only a simplistic and generalised view of politics concluding that all is guided by top-down patronage, looking at local relations through in-depth research reveals a room for manoeuvre for those who have the resources and ingenuity to play the system.

These brief and rather partial summaries cannot do justice to the richness of the papers. If you want to hear more, there is a recording of the presentations and the discussions here. As noted, each in different ways contribute to our evolving understandings of livelihoods after land reform, and demonstrate the importance of diverse methodological approaches in capturing the nuance and diversity. These three papers, all emerging from PhD studies at the University of Edinburgh, are examples of a growing array of research on different themes in different places. They add together to an impressive dataset that has yet to be fully grasped by policymakers, donors and other commentators, including many academic 'authorities' on Zimbabwe.

A couple of years ago, I compiled a list of research projects on 'fast-track' land reform of different sorts, many deriving from PhD and MA degrees, and mapped them. The coverage then was impressive, and I am sure has extended much further since. Yet, despite this growing body of work, we hear again and again misleading commentary and inappropriate conclusions being drawn on land reform in Zimbabwe. But building on the earlier work, including ours in Masvingo, we now have an impressive set of insights, offering nuance and perspective on our overall assessment of Zimbabwe’s land reform. I hope this blog will continue to be a space for sharing these results with a wider audience. So if you are doing a study, and have some results to share, even if preliminary, do let me know!

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

The three panellists all reported on new research in the now not-so-new resettlements, representing different geographic areas, and diverse methodologies. All looked at how new livelihoods are being carved out following land reform in A1 sites. This included in-depth reflections on the relationships between farmers and farmworkers, a quantitative assessment of production outcomes across sites compared to communal and old resettlement areas, and an analysis of how farm and off-farm livelihood opportunities are combined in a mining area.

The session kicked off with an excellent paper by Leila Sinclair-Bright who discussed the changing social relations between 'new farmers' on an A1 resettlement area in Mazowe and farmworkers. Through a deep, focused ethnographic approach she looked at changing notions of 'belonging', and the way livelihoods are negotiated. A case of a chief's court dispute over land highlighted many of the dynamics. For, while the farmworkers were accepted as part of the farm community, and even incorporated into the cultural fabric of life through their as 'sahwira' at burials, when a group tried to claim formally the land that they had been cultivating this was rejected by the A1 farmers.

'Belonging' had its limits, and the new farmers tried to circumscribe this, arguing that as 'foreigners' (many had Malawian origins several generations back), their role was not as land owners but labourers. That the farmworkers had been bargaining hard on wages and opting for alternate livelihoods had played into this tension. Certainly the emerging forms of 'belonging' differ dramatically from that described by Blair Rutherford in the pre-land reform era, but the cultural politics of farmworker-farmer relations are as live as ever, often flaring up into disputes of this sort.

Leila's paper highlighted the value of really in-depth analysis of cases to uncover the textured dynamics of change on the farms. We have been subjected to far too much simplistic analysis, often based on spurious statistics, on farmworkers, but this sort of work really provides a much-needed qualitative insight that is immensely revealing. As the new social, political and economic relations are negotiated on the new farms, new bargains and accommodations will be struck, and this will require innovations in institutional and cultural practices; sometimes drawing on traditional norms, but in other cases requiring new deals to be struck.

Taking a very different approach, Gareth James offered an overview of some of his impressive survey work across three districts in Mashonaland/Manicaland, involving a sample of over 600. This involved a large sample extending the classic work by Bill Kinsey and colleagues that tracked the fortunes of 'old resettlement' area farmers, comparing these to their neighbours in the communal areas (see our Masvingo work on this, in a recent blog series). Gareth has developed a sample in A1 farming areas, and looked at a range of factors. This presentation focused on 'outcomes' and in a series of graphs he showed how the A1 farmers on average outperformed both the old resettlement area and communal area farmers across a range of criteria. As younger, more educated, more capitalised farmers, they had higher outputs and yields of major crops (maize, cotton, tobacco), applied more inputs and achieved higher incomes. He offered a listing of the constraints faced too, which included a familiar array focused on the challenges of accessing farming inputs and labour. For those of us who primarily work in the drier south of the country, the production statistics were impressive. Across the two seasons studied (both of which were not good seasons), the A1 farmers achieved an average output of around 6 tonnes of maize. Taking the standard figure of annual consumption requirements of 1 tonne per family, this means around 5 tonnes could be sold, and contribute to a dynamic of investment and accumulation that Gareth described. This was of course added to by the often impressive outputs of tobacco. Averages of course only tell one part of the story, and as he pointed out there is much variation. As we have seen in Masvingo, these dynamics create new patterns of differentiation and associated class formation in the new resettlements, with major consequences for agrarian social relations and longer term change. There was insufficient time in the presentation to explore these issues, but the results are tantalising, and the overall output statistics impressive. Of course there are qualifications, and some of these were discussed. Is this a temporary boom, based on the 'mining' of the soil? Will the success attract more and more people to area, and so undermine per capita success as land and outputs are shared among more and more? Did the new settlers manage to outcompete their neighbours through preferential access to inputs, offered through political patronage? All of these factors are important, but do not undermine the overall story of a production boom, with major opportunities for accumulation in the new resettlements.

The final paper by Grasian Mkodzongi reflected on his work in Mhondoro Ngezi in Midlands Province. Here A1 and A2 resettlement areas are in close proximity to the major Zimplats mining complex. Grasian's paper concentrated on the relationships between farming and mining, as mediated through labour contracts, business opportunities and political connections. In addition to the large-scale mine there are many other smaller mining operations, for gold and other minerals that provide opportunities for others. The paper focused on the social and political negotiation of the farming-mining relationship, based on a number of cases. New farmers are able to insert themselves into the economic activity associated with Zimplats, supplying inputs (such as silica found on their farms) as well as profiting from upstream aspects of the value chain. Farmers have used the politically-charged debate around 'indigenisation' to their advantage, manipulating the rhetoric and demanding economic benefits. This sets up new political and economic relationships between the farms and the mine that are played out through local political dramas. The story is immensely complex and fast evolving, but it offers an insight into how, at the local level, new economic relations with capital are being negotiated, and how a very particular political dynamics and discourses influence this. Contrary to analyses that offer only a simplistic and generalised view of politics concluding that all is guided by top-down patronage, looking at local relations through in-depth research reveals a room for manoeuvre for those who have the resources and ingenuity to play the system.

These brief and rather partial summaries cannot do justice to the richness of the papers. If you want to hear more, there is a recording of the presentations and the discussions here. As noted, each in different ways contribute to our evolving understandings of livelihoods after land reform, and demonstrate the importance of diverse methodological approaches in capturing the nuance and diversity. These three papers, all emerging from PhD studies at the University of Edinburgh, are examples of a growing array of research on different themes in different places. They add together to an impressive dataset that has yet to be fully grasped by policymakers, donors and other commentators, including many academic 'authorities' on Zimbabwe.

A couple of years ago, I compiled a list of research projects on 'fast-track' land reform of different sorts, many deriving from PhD and MA degrees, and mapped them. The coverage then was impressive, and I am sure has extended much further since. Yet, despite this growing body of work, we hear again and again misleading commentary and inappropriate conclusions being drawn on land reform in Zimbabwe. But building on the earlier work, including ours in Masvingo, we now have an impressive set of insights, offering nuance and perspective on our overall assessment of Zimbabwe’s land reform. I hope this blog will continue to be a space for sharing these results with a wider audience. So if you are doing a study, and have some results to share, even if preliminary, do let me know!

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

To improve access to seeds for African farmers, we need more than technical solutions

|

| Inside the agro-vet by STEPS Centre (Flickr), used with kind permission |

Despite huge investment from governments and donors in seed sector development in Africa over the better half of a century, access to quality seed remains a great challenge for smallholder farmers across the continent.

Addressing this challenge is a complex task, and requires an integrated, multidisciplinary and innovation systems approach. Certain aspects of the greater challenge may be best addressed at regional level, through the collaboration of countries, experts, seed programmes, and their associated organizations and institutions in the public and private domains.

A select number of challenge areas have been prioritised for deeper exploration and intervention through an action-oriented research and learning approach during the Piloting Phase of the Comprehensive Programme on Integrated Seed Sector Development in Africa.

These include:

- Promoting entrepreneurship: ISSD Africa sees a challenge in promoting entrepreneurship in more than just the typical seed value chains, such as maize.

- Improving access: unless we improve access to those varieties developed in the public domain, they are destined to stay on the shelf.

- Impacts of global commitments: African seed sector stakeholders, in government, in development and in industry, need to be more critical in their evaluation of global commitments in terms of the implications upon national seed sector development strategies and their domestication into local realities.

- Coherence and strategy: last on the agenda of the Piloting Phase is addressing the challenge of keeping national investments in the seed sector coherent, cohesive and strategic in meeting the ambitious targets of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) and the African Seed and Biotechnology Programme (ASBP).

For this we require integration of technical and social systems, technologies and institutions, knowledge and good will, if we are to be successful in addressing such a complex challenge in a changing environment.

By Gareth Borman, Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR

Thursday 11 September 2014

Inclusive business model? The Case of Sugarcane Production in Tanzania

Since the emergence of the “land grab” phenomenon in the mid-2000s, alternative approaches to land-based investments have been developed and tested to mitigate the often significant and adverse impacts on rural people of such grabs while still supporting foreign direct investments, particularly in agriculture, for economic development in African countries.

The use of more inclusive business models is one approach. These models aim to ensure that the existing land users do not lose their rights to access, control and own land. They are meant to empower communities to have a voice in business decision making processes and share benefits and risks resulting from the business activities.

As suggested in a number of voluntary guidelines, including the African Union Framework and Guidelines, and the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security, the rights of women and indigenous communities to access, control and own land are critical to local development. Research clearly indicates that in areas where women have access and control over the land they farm, they earn a significantly more income and have greater power in family decision making processes. Inclusive business models are crucial in ensuring these rights are upheld.

‘Plantation farming’ refers to a system in which a single operator or company (sometimes with partners) is responsible for organizing the economic activities of production, processing and marketing. The term ‘outgrower farming’ includes small-scale, medium and large-scale farmers supplying their agricultural produce to a processer or a miller. This relationship is based on specific contractual obligations, for example, that the company will buy farmers’ produce and provide them with inputs and training, while farmers commit to supply produce in specified quantities and quality.

The Case of Kilombero Sugar Company Limited in Tanzania

To illustrate, most of the existing sugarcane millers in sub-Saharan Africa have leased or owned plantations, sugarcane crushing and processing facilities, while the sugarcane outgrowers own or rent their farmland, and supply their produce and some labor to the company. The miller markets, processes and distributes the final products such as sugar, molasses and spirits. At the end, both the miller and the outgrowers share the final proceeds in the pre-agreed manner. Overall, agricultural business models which utilize partnerships between plantations and outgrowers remain more successful than single large-scale investments in land or plantations.

The sugarcane production model used by the Kilombero Sugar Company Limited (KSCL) in Kilombero District, Tanzania, provides an example of some elements of inclusive business models and their challenges. KSCL has been partnering with sugarcane smallholder farmers to produce sugarcane that is processed, marketed and distributed by the miller (KSCL). The partnership is based on a Cane Supply Agreement (CSA) which is signed between the company and the farmers’ associations every three years, and may be amended every harvesting season if the need arises. Individual outgrowers cannot sign contracts with the company. Instead, they participate through local farmers’ associations, of which there are now 15 in the Kilombero District.

How it works

The CSA spells out the division of proceeds, and it requires the company to pay the outgrower for the sugarcane delivered to the company on the 15th day of the following month. For the year 2013/14, outgrowers earned US$35.6/tonne, before adjustments for sucrose levels and actual sales are made. Based on these adjustments, outgrowers are paid less if the sucrose level of their cane is too low; and all growers are paid based on final sales. Payment is done on the ratio of 57 percent to 43 percent of the profits for outgrowers and the company, respectively.

The outgrowers can participate in the sugarcane production business with as little as one acre of land. Since each farmer has full control of his or her land, he or she is still free to lease out such land or turn it to the production of other crops such as rice or maize – all suitable in the area, although their production is now affected by birds nesting in sugarcane fields.

At the moment, KSCL is the largest miller in Tanzania; it runs two irrigated estates with a total 8,022 hectares and two factories. It buys sugarcane from over 8,000 registered outgrowers who own individual sugarcane farms amounting to 11,900 hectares. Currently, outgrowers supply 43 percent of the total sugarcane processed by the company annually. In 2013/14 the company produced 116,495 tonnes of sugar, about 40 percent of the total sugar produced in the country. The company, through outgrowers’ associations, has managed to mobilize a large number of outgrowers to put their farmland into sugarcane growing fields, and attracted some donor support to finance the maintenance of both the estate and outgrowers’ infrastructure.

This partnership is not without challenges. The inadequately planned and executed expansion of sugarcane production in the area is now causing problems for the outgrowers and the company. This is because the production levels have overshot the company’s processing capacity, leaving farmers with sugarcane that is unharvested and unsold, and no options rather than being indebted. Recently, farmers have also registered complaints around the measurements of their sugarcane weights and sucrose levels by the company.

This has resulted in the phenomenon of ‘commuter families’; that is, families commuting between the sugarcane producing villages to other villages in search of land to produce food crops. This can negatively affect families, as their children are either left alone or with only one parent.

Problems are aggravated by increased importation of cheap foreign sugar. Although, the importation of foreign sugar is necessary to fill the gap left by local producers, levy-free or subsidized sugar imports are far cheaper than locally produced sugar.

Actions Needed

To address these challenges, required immediate actions include improved transparency and accountability within the sugar board of Tanzania to avoid excessive importation of sugar. A transparent measurement system for farmers’ sugarcane weights and sucrose levels is also needed, preferably one approved by both the farmers’ representatives and those of the company. Also, efforts should be made to ensure KSCL has the capacity to process all produced sugarcane each season. Otherwise, markets for other crops, such as rice, should be improved in the area to give farmers an opportunity to turn the extra sugarcane farms to rice producing fields.

Some lessons from the KSCL business model are critical for Tanzania’s new initiatives such as the development of the Southern Agriculture Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) and Big Results Now (BRN) – all of which include the expansion of sugarcane farming as a priority crop. These new initiatives need to ensure that the positive aspects of the hybrid model -- such as few barriers to enter the sugar business, and the clear and respected division of business proceeds between the agribusiness and outgrowers -- are emulated.

Important takeaways from this model include attention to the structure of resource ownership between the miller and outgrowers, institutional arrangements, and the contract flexibility which allows both partners to negotiate sugarcane prices whenever there is a need to do so. Assuming the outgrower associations have access to adequate market information, this helps every partner in the business to maximize benefits and minimize business related risks. However, it is also critical to note that compared to the company, local farmers remain weak partners and effort is needed to ensure they have the knowledge and capacity to be able to negotiate reasonable terms with the company.

Is bigger better?

The model suggests that for agricultural investments to work, an investor does not necessarily need large plots of land of up to 50,000 hectares as suggested in SAGCOT plans, but rather a moderate amount of land which could also encourage an investor to look for extra outputs from neighboring farmers as has happened with KSCL. In fact, all operating sugar mills in Tanzania have plantations of less than 10,000 hectares.

In addition, during the implementation of SAGCOT and BRN, proper land use planning must be done to ensure that the land allocated to nucleus and outgrower farms for cash crops includes food producing zones. In this way, the issues of food insecurity and farmers commuting from one location to the other in search of food producing land will be addressed.

Lastly, it is critical to understand that inclusive business models do not operate in a vacuum; rather they require enabling policy, legal and institutional frameworks that are efficiently and effectively executed.

By Emmanuel Sulle, researcher, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, Souch Africa

Related Resources:

Opportunities and Challenges in Tanzania’s Sugar Industry: Lessons for SAGCOT and the New Alliance (pdf) Future Agricultures Policy Brief 76, by Emmanuel Sulle

Blog: 'Commuter farmers’ in Tanzania’s valley of sugar and rice

This article first appeared on the Focus on Land website.

The use of more inclusive business models is one approach. These models aim to ensure that the existing land users do not lose their rights to access, control and own land. They are meant to empower communities to have a voice in business decision making processes and share benefits and risks resulting from the business activities.

As suggested in a number of voluntary guidelines, including the African Union Framework and Guidelines, and the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security, the rights of women and indigenous communities to access, control and own land are critical to local development. Research clearly indicates that in areas where women have access and control over the land they farm, they earn a significantly more income and have greater power in family decision making processes. Inclusive business models are crucial in ensuring these rights are upheld.

An inclusive business model is one in which the elements of resource ownership, voice, risks and rewards are clearly defined, understood and respected by all parties engaged in such a business.

Currently, a range of existing business models used in the production, processing, marketing and distribution of both cash and food crops is considered inclusive. The most commonly referred to “inclusive business model” is a hybrid model - a combination of plantation and outgrowers.‘Plantation farming’ refers to a system in which a single operator or company (sometimes with partners) is responsible for organizing the economic activities of production, processing and marketing. The term ‘outgrower farming’ includes small-scale, medium and large-scale farmers supplying their agricultural produce to a processer or a miller. This relationship is based on specific contractual obligations, for example, that the company will buy farmers’ produce and provide them with inputs and training, while farmers commit to supply produce in specified quantities and quality.

The Case of Kilombero Sugar Company Limited in Tanzania

To illustrate, most of the existing sugarcane millers in sub-Saharan Africa have leased or owned plantations, sugarcane crushing and processing facilities, while the sugarcane outgrowers own or rent their farmland, and supply their produce and some labor to the company. The miller markets, processes and distributes the final products such as sugar, molasses and spirits. At the end, both the miller and the outgrowers share the final proceeds in the pre-agreed manner. Overall, agricultural business models which utilize partnerships between plantations and outgrowers remain more successful than single large-scale investments in land or plantations.

However, it is important to note that almost all ‘inclusive’ models have shortcomings—some serious enough to disqualify them as inclusive business models.

How it works

The CSA spells out the division of proceeds, and it requires the company to pay the outgrower for the sugarcane delivered to the company on the 15th day of the following month. For the year 2013/14, outgrowers earned US$35.6/tonne, before adjustments for sucrose levels and actual sales are made. Based on these adjustments, outgrowers are paid less if the sucrose level of their cane is too low; and all growers are paid based on final sales. Payment is done on the ratio of 57 percent to 43 percent of the profits for outgrowers and the company, respectively.

The outgrowers can participate in the sugarcane production business with as little as one acre of land. Since each farmer has full control of his or her land, he or she is still free to lease out such land or turn it to the production of other crops such as rice or maize – all suitable in the area, although their production is now affected by birds nesting in sugarcane fields.

At the moment, KSCL is the largest miller in Tanzania; it runs two irrigated estates with a total 8,022 hectares and two factories. It buys sugarcane from over 8,000 registered outgrowers who own individual sugarcane farms amounting to 11,900 hectares. Currently, outgrowers supply 43 percent of the total sugarcane processed by the company annually. In 2013/14 the company produced 116,495 tonnes of sugar, about 40 percent of the total sugar produced in the country. The company, through outgrowers’ associations, has managed to mobilize a large number of outgrowers to put their farmland into sugarcane growing fields, and attracted some donor support to finance the maintenance of both the estate and outgrowers’ infrastructure.

This partnership is not without challenges. The inadequately planned and executed expansion of sugarcane production in the area is now causing problems for the outgrowers and the company. This is because the production levels have overshot the company’s processing capacity, leaving farmers with sugarcane that is unharvested and unsold, and no options rather than being indebted. Recently, farmers have also registered complaints around the measurements of their sugarcane weights and sucrose levels by the company.

Yet, as the sugarcane business becomes more lucrative, elites are buying out land from small farmers, and outgrowers have turned most of their farmland into sugarcane fields, increasing land scarcity for food crops in the area.

Problems are aggravated by increased importation of cheap foreign sugar. Although, the importation of foreign sugar is necessary to fill the gap left by local producers, levy-free or subsidized sugar imports are far cheaper than locally produced sugar.

Actions Needed

To address these challenges, required immediate actions include improved transparency and accountability within the sugar board of Tanzania to avoid excessive importation of sugar. A transparent measurement system for farmers’ sugarcane weights and sucrose levels is also needed, preferably one approved by both the farmers’ representatives and those of the company. Also, efforts should be made to ensure KSCL has the capacity to process all produced sugarcane each season. Otherwise, markets for other crops, such as rice, should be improved in the area to give farmers an opportunity to turn the extra sugarcane farms to rice producing fields.

Some lessons from the KSCL business model are critical for Tanzania’s new initiatives such as the development of the Southern Agriculture Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) and Big Results Now (BRN) – all of which include the expansion of sugarcane farming as a priority crop. These new initiatives need to ensure that the positive aspects of the hybrid model -- such as few barriers to enter the sugar business, and the clear and respected division of business proceeds between the agribusiness and outgrowers -- are emulated.

Important takeaways from this model include attention to the structure of resource ownership between the miller and outgrowers, institutional arrangements, and the contract flexibility which allows both partners to negotiate sugarcane prices whenever there is a need to do so. Assuming the outgrower associations have access to adequate market information, this helps every partner in the business to maximize benefits and minimize business related risks. However, it is also critical to note that compared to the company, local farmers remain weak partners and effort is needed to ensure they have the knowledge and capacity to be able to negotiate reasonable terms with the company.

Is bigger better?

The model suggests that for agricultural investments to work, an investor does not necessarily need large plots of land of up to 50,000 hectares as suggested in SAGCOT plans, but rather a moderate amount of land which could also encourage an investor to look for extra outputs from neighboring farmers as has happened with KSCL. In fact, all operating sugar mills in Tanzania have plantations of less than 10,000 hectares.

In addition, during the implementation of SAGCOT and BRN, proper land use planning must be done to ensure that the land allocated to nucleus and outgrower farms for cash crops includes food producing zones. In this way, the issues of food insecurity and farmers commuting from one location to the other in search of food producing land will be addressed.

Lastly, it is critical to understand that inclusive business models do not operate in a vacuum; rather they require enabling policy, legal and institutional frameworks that are efficiently and effectively executed.

By Emmanuel Sulle, researcher, Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, Souch Africa

Related Resources:

Opportunities and Challenges in Tanzania’s Sugar Industry: Lessons for SAGCOT and the New Alliance (pdf) Future Agricultures Policy Brief 76, by Emmanuel Sulle

Blog: 'Commuter farmers’ in Tanzania’s valley of sugar and rice

This article first appeared on the Focus on Land website.

Tuesday 9 September 2014

Complex Adaptive Systems & health: new resources

In June 2014, Future Health Systems (FHS) and the STEPS Centre co-hosted a workshop exploring Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) approaches to health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

In June 2014, Future Health Systems (FHS) and the STEPS Centre co-hosted a workshop exploring Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) approaches to health systems strengthening in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

FHS and STEPS are particularly concerned with policies, programs, and individual level interventions promote and protect people's health and wellbeing, particularly vulnerable and disadvantaged populations.

The workshop was designed mainly to build capacity among both consortia on specific methods for working with and understanding CAS.

Read the workshop summary

The Future Health Systems team has produced a summary from the workshop with

- A brief run-down of methods relevant to Complex Adaptive Systems

- Video introductions from Taghreed Adam and Ben Ramalingam (YouTube playlist)

- Full video of 7 presentations from the workshop (YouTube playlist)

- 7 blogposts on complexity approaches & their use in health systems research

Blog posts

Two articles by STEPS members in this series have also been re-posted on the STEPS blog:

- 'Innovation histories': capturing legacy & learning from long-term programmes by Annie Wilkinson

- New methods needed: How can complexity science help us to understand pluralistic health systems? by Gerry Bloom

Further reading

The Future Health Systems website has a theme on Complex Adaptive Systems, drawing together all FHS work in this area.

For more projects and publications in this area, see our Health & Disease Domain page.

The book Transforming Health Markets in Asia and Africa: Improving quality and access for the poor documents the innovative approaches designed to address the problems associated with unregulated health markets, and proposes a framework for understanding health market systems and outcomes.

Monday 8 September 2014

New narratives on Zimbabwe’s land reform: a panel at the African Studies Association Conference this week at the University of Sussex

New research from Zimbabwe will be shared at a double panel session at the UK African Studies Association on Wednesday this week. This is being held at the University of Sussex on 10 September between 9 and 12.30 (with a break!). The session has been organised by Gareth James of Edinburgh University, and I will chair.

Zimbabwe's land reform that unfolded from 2000 has been intensely controversial, and remain so. But 14 years on there is a wider array of research to draw from in order to make more balanced and informed conclusions on outcomes and implications.

The work published in Zimbabwe's Land Reform: Myths and Realities, showed how some farmers who gained land through the land reform in Masvingo did remarkably well – accumulating, investing and improving production. Others have pointed to the 'tobacco boom' that has brought significant riches to those in the Highveld tobacco areas. Such successes have not universally been the case however. Land in some areas remains poorly utilised, some larger scale farmers have failed to invest, and political elites have captured land but not put it into production.

The panel, "New narratives and emerging issues in the Zimbabwe land debate", will provide an opportunity to reflect on new research conducted by Zimbabwean and European researchers in the last few years in different parts of the country. The six papers that will be presented and discussed are listed below.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Zimbabwe's land reform that unfolded from 2000 has been intensely controversial, and remain so. But 14 years on there is a wider array of research to draw from in order to make more balanced and informed conclusions on outcomes and implications.