by Jake Winn

by Jake WinnValentine’s Day is traditionally an occasion to celebrate love, but for far too many worldwide, this is just another reminder of the daily repression they face, the secrets they hold and the love they cannot express.

The LGBTQ community in the former Soviet republic of Azerbaijan is currently mourning the loss of one of its bright, young leaders, Isa Sahmarli. Sahmarli, the co-founder of Azad LGBT took his own life on 22 January 2014. Although only 20 years of age, Sahmarli was one of the country’s most prominent and openly gay activists, and as such, his death sparked debate about LGBTQ rights in Azerbaijan. These debates run alongside a deeper critique among those affected by Shamarli’s death, both within and beyond Azerbaijan’s borders.

This critique, as explored through the Sexuality, Poverty and Law (SPL) Programme at IDS, centres on the powerful ways that policies reach into the most intimate and everyday spaces of people’s lives and their relationships – through laws and policies, for example, that regulate people’s bodies along sex binaries, that limit people’s capacity to exert autonomy in their sexual relationships, that criminalise certain expressions of sexuality and restrict the kind of education or employment opportunities available. These issues are brought together in the most recent publication from the SPL Programme, which offers a synthesis of five legal case studies.

In addition to looking at how policies and the law regulate people’s bodies and sexualities and the material implications for their livelihoods, it is important to consider the strategies that people draw on to raise awareness and challenge the spaces in which they experience social, economic and political marginalisation.

In Azerbaijan it is primarily through online digital spaces that people and organisations are safely able to offer support and resources to those who experience these multiple and intersecting forms of marginalisation in their home, workplace, or school, for example.

It is Sahmarli’s death, in particular, that has prompted those closest to him to turn to online digital spaces in order to seek support and begin a dialogue about the repression faced by LGBTQ people and allies in Azerbaijan. As part of this process, they have launched an online photo campaign entitled ‘SevgiElə Sevgidir’, translated into English as ‘Love Is Love’, to pay tribute to their friend and leader and send a message to other LGBTQ individuals in the country and abroad to say, ‘You are not alone’. On Valentines Day, this online photo campaign will release hundreds of photographs of people from all over the world, all saying ‘Love is Love’, through online activist sites in solidarity with LGBTQ people in Azerbaijan.

When considering sexuality through the lens of the law, historic and contemporary geopolitics become salient: in order to join the Soviet Union, in 1920, Azerbaijan was required to introduce Soviet laws criminalizing homosexuality. It was only when seeking to join the Council of the European Union in 2000, that Azerbaijan finally repealed this law (Article 121). In practice, however, the historic policy infrastructure that flowed from Article 121 remains firmly in place. Although same-sex relationships are not legally punishable, social stigma persists and economic discrimination is entrenched in policies that do not offer the same legal protections to same-sex partners - or their families, as heterosexual partners.

Looking out from Azerbaijan to its neighbouring countries, homosexuality is illegal in adjacent Iran, is likely to become illegal in fellow ex-Soviet state Kazakhstan, and as noted previously in the KNOTS blog on the opening of the Winter Olympics in Sochi, queer rights in neighboring Russia have been undermined by the anti-propaganda law.

Despite the absence of these official, draconian laws in Azerbaijan, LGBTQ people lack political recognition and legal protection against abuses such as public harassment and workplace discrimination (for example, see this local study done by Nefes, an LGBT group in Azerbaijan). Social stigma is deeply entrenched and treatment of LGBTQ people remains severely oppressive, especially outside of the capital city of Baku where confidential spaces for support are almost nonexistent. Many in the country still believe that homosexuality is a disease that can be cured. Sahmarli himself revealed last year that,“though psychologists explained it to my family, they still call it an illness.” His family disowned him after coming out. He had to move out and his mother and sister only ever talked to him in attempts to “cure” him.

The dangers of being open given these high levels of stigmatization are not the only reason that Azerbaijan’s LGBTQ community has turned towards the web for support and mobilization. Eerily reminiscent of the recent restrictions Russia imposed on NGOs, the electoral authoritarian state of Azerbaijan recently signed into law an amendment that provides the authorities with various triggers for temporarily suspending and permanently banning national and foreign NGOs working in the country. Already one of the most corrupt and politically repressive regimes in the world according to Freedom House, such legislation serves as further motivation for rights groups to get off the streets and turn to the web.

In a recent publication, Katy Pearce explored the opportunities in Azerbaijan for digital political activism, claiming that such groups are ‘leveraging social media to build audiences and engage in [connective] action’. These become virtual spaces to build support and share information. Despite still being in the public domain and thus vulnerable to resistance, she asserts that these ‘networks are light on their feet’ and ‘create a web that is more difficult to destroy’. Such networking is not limited to the LGBTQ community. Youth activist groups like NIDA, themselves the victims of harsh political censuring, have been using social media for some time to voice dissatisfaction with the ruling government. So, when it comes to future implications for this burgeoning medium of activism, Sebastián Valenzuela‘ found that social media use for political opinion expression and activism were significant predictors of protest behavior’.

Virtual campaigns like ‘Love is Love’ may be a sign of things to come.

Hidden and invisible powers, fueled by government heavy-handedness and social mistrust stemming back to the Soviet era, are currently dictating popular opinion regarding LGBTQ rights. But Azerbaijan’s LGBTQ community and its supporters are fighting back, claiming the digital world as its space to provide support and campaign for equality.

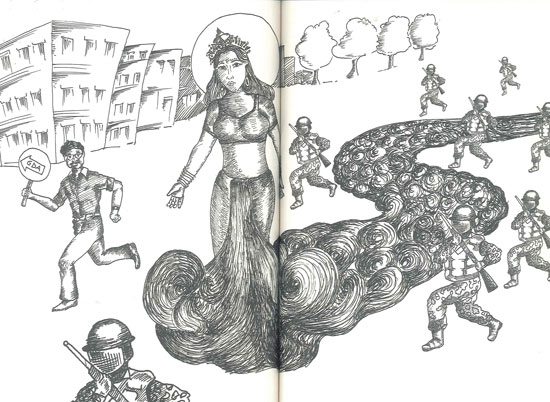

It is through these social media outlets that the true difference between law and policy in Azerbaijan is being revealed. Global pressure and a national desire for inclusion into the Council of Europe led to a change in Azerbaijan’s law in 2000, decriminalizing homosexuality. To an outsider, this was progress. In reality, more inclusive policies never followed; it was all smoke and mirrors. Now, the potential success of international campaigns like ‘Love Is Love’ bring hope and makes us ask: How much longer will the LGBTQ community of Azerbaijan, and countries like it, have to live in the shadows? When will we all be able to celebrate Valentine’s Day, together?

|

| In memory of Isa Sahmarli (30/4/1993-22/1/14) |