This week's STEPS Centre seminar (27th Feb, 1-2.30. IDS), will be with Alex Arnall of the University of Reading. Alex will discuss how, in one area of Mozambique, narratives about adapting to climate change are being used to justify the resettlement of farmers to higher, less fertile ground.

Tuesday, 26 February 2013

The Unbearable Whiteness of Being. Reflections on white farming in Zimbabwe

This is the main title of a new book by Rory Pilossof from the University of Pretoria and published by Weaver Press in Zimbabwe. The book documents the voices of white farmers in Zimbabwe through an analysis of the contributions to the CFU's magazine, The Farmer, especially in the period after the land invasions, a reading of the now burgeoning post 2000 literature by white Zimbabweans, and through interviews with members of the breakaway Justice for Agriculture (JAG) group.

In addition to the brilliant title (although not the only use it seems), it is a fascinating read giving a much needed account of this period from the perspective of those who lost land. The title of course echoes Garcia Marquez's famous book, and there is a touch of magical realism in some of the vignettes in this text too. Magical realism as a genre is defined as when "a realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe".

The events that unfolded from 2000 with the mass invasion of farms, including outbreaks of sometimes extreme violence in places, are certainly very real. The tales told are harrowing and convincing: somehow more so than the journalistic accounts of Peter Godwin and co. They mix the mundane with the dramatic, and are set in life stories that are very peculiarly Zimbabwean. The appendix of profiles of those interviewed (mostly from Mashonaland) is particularly enlightening. Yet the unreal and strange is also there. These testimonies are from the twenty-first century, but with many views and perspectives belonging to the nineteenth.

As Pilossof recounts, farmers who were willing to speak (obviously a selective sample) were so caught up in the traumatic events that their prejudices were plain to see, and not hidden from an interviewer who, as someone with white skin, was assumed to be sympathetic and of similar views. Strange is perhaps too calm an epithet: to many outside the narrow, isolated social circles of white rural Zimbabwe, such views are shocking; what Pilossof calls 'condescending paternalism' and 'racist ramblings' in one book he reviews. Together these insights expose of course the extraordinary social and political separation that many in the white farming community got caught in, even 20 years after Independence.

The cultural mores and political biases, and the racial tinge to everything are well documented in David Hughes' book, with its analysis of landscape, conservation and farming. But somehow this book is more direct. Pilosoff tries to be balanced, and clearly he is affected by many of the stories told, but he also is forced to comment on what he hears.

The pervasive 'white myopia', as Pilossof terms it, was upheld by a series of myths. These "served the important function of allowing white farmers to live at ease with the scale of their land holdings, and to believe that they had done no wrong by buying into a system that so obviously segregated black from white". This was bolstered by the view that farmers were apolitical, and that all they did was farm, despite for many representing the unfinished business of the liberation war. The book identifies a number of 'myths' of white farming: how farmers tirelessly struggled to tame an empty and unforgiving bush, how they had equally to control and discipline their workers who were lazy and deceitful, and how the productivity of white farming was the result of such disciplined hard work and investment. As he notes, no mention is made in the accounts of course of the massive government subsidies that kept most white farming afloat, nor the terrible conditions most farm labour suffered.

The accounts offer glimpses into a worldview overshadowed by patronising superiority. People emphasised how they loved and cared for their special servants and farm managers, yet despised and feared their land hungry neighbours, deemed to be 'gooks' and 'terrs'. There is no narrative of belonging or of equality, just one struck through with racial superiority. It is no wonder that most found the land reform utterly surprising and wholly reprehensible. It ran against all things they upheld. Despite being hard working and sometimes quite successful farmers, many simply did not realise that things had to change, and this stubborn resistance to the 'wind of change' (40 years after MacMillan gave the famous speech in the South African parliament) is witness to the extraordinarily narrow outlook that many held.

Pilossof concludes:

"While many claimed to have changed their identity, to be Zimbabwean rather than Rhodesian, and to be 'white Africans', this is tempered by their use of the word 'African' to always and only to refer to blacks. As such, white farmers in Zimbabwe are 'orphans of empire', unable to progress past this state of being thus 'become' Zimbabwean".

In some ways the book could be critiqued as unbalanced. Pilossof found it difficult to gain access to information, and many people would not speak, so charged was the atmosphere in the mid 2000s. His interviews are with an extreme group – JAG – which many would say was not part of the mainstream, although it was plentifully supported by foreign donors. He also interviewed people in the heart of Mashonaland where the land invasions were most contested, and where violence was most prominent. Also, after 2000 The Farmer was in its dying days, when it was most shrill in its criticisms of the land reform, rejecting the more conciliatory stances of some within the CFU. He also uses the sometimes bizarre white memoirs and biographies as sources, which many would argue offer particularly odd interpretations of white Zimbabwe. He therefore did not speak to those realists and pragmatists who perhaps saw the land reform as the 'writing on the wall', something that was inevitable and that had to be accommodated. He did not discuss with those who did not have an escape route to town, with alternative non-farm businesses, and so did not speak to those who sought compromises and accommodations on their farms. And he did not speak to those few who actually supported land reform, even if not the form it took. This is another dimension of white farmers' voices that needs to be told, and awaits another book.

But such gaps do not undermine the value of the book, as the array of perspectives garnered while showing variation and lack of clear consensus, definitely shows a particular and well recognised discourse. As a documentation of the perhaps inevitable end of an era spawned by a brutal form of settler colonialism it provides a rather sad and telling doorstop to a troubled period.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

In addition to the brilliant title (although not the only use it seems), it is a fascinating read giving a much needed account of this period from the perspective of those who lost land. The title of course echoes Garcia Marquez's famous book, and there is a touch of magical realism in some of the vignettes in this text too. Magical realism as a genre is defined as when "a realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe".

The events that unfolded from 2000 with the mass invasion of farms, including outbreaks of sometimes extreme violence in places, are certainly very real. The tales told are harrowing and convincing: somehow more so than the journalistic accounts of Peter Godwin and co. They mix the mundane with the dramatic, and are set in life stories that are very peculiarly Zimbabwean. The appendix of profiles of those interviewed (mostly from Mashonaland) is particularly enlightening. Yet the unreal and strange is also there. These testimonies are from the twenty-first century, but with many views and perspectives belonging to the nineteenth.

As Pilossof recounts, farmers who were willing to speak (obviously a selective sample) were so caught up in the traumatic events that their prejudices were plain to see, and not hidden from an interviewer who, as someone with white skin, was assumed to be sympathetic and of similar views. Strange is perhaps too calm an epithet: to many outside the narrow, isolated social circles of white rural Zimbabwe, such views are shocking; what Pilossof calls 'condescending paternalism' and 'racist ramblings' in one book he reviews. Together these insights expose of course the extraordinary social and political separation that many in the white farming community got caught in, even 20 years after Independence.

The cultural mores and political biases, and the racial tinge to everything are well documented in David Hughes' book, with its analysis of landscape, conservation and farming. But somehow this book is more direct. Pilosoff tries to be balanced, and clearly he is affected by many of the stories told, but he also is forced to comment on what he hears.

The pervasive 'white myopia', as Pilossof terms it, was upheld by a series of myths. These "served the important function of allowing white farmers to live at ease with the scale of their land holdings, and to believe that they had done no wrong by buying into a system that so obviously segregated black from white". This was bolstered by the view that farmers were apolitical, and that all they did was farm, despite for many representing the unfinished business of the liberation war. The book identifies a number of 'myths' of white farming: how farmers tirelessly struggled to tame an empty and unforgiving bush, how they had equally to control and discipline their workers who were lazy and deceitful, and how the productivity of white farming was the result of such disciplined hard work and investment. As he notes, no mention is made in the accounts of course of the massive government subsidies that kept most white farming afloat, nor the terrible conditions most farm labour suffered.

The accounts offer glimpses into a worldview overshadowed by patronising superiority. People emphasised how they loved and cared for their special servants and farm managers, yet despised and feared their land hungry neighbours, deemed to be 'gooks' and 'terrs'. There is no narrative of belonging or of equality, just one struck through with racial superiority. It is no wonder that most found the land reform utterly surprising and wholly reprehensible. It ran against all things they upheld. Despite being hard working and sometimes quite successful farmers, many simply did not realise that things had to change, and this stubborn resistance to the 'wind of change' (40 years after MacMillan gave the famous speech in the South African parliament) is witness to the extraordinarily narrow outlook that many held.

Pilossof concludes:

"While many claimed to have changed their identity, to be Zimbabwean rather than Rhodesian, and to be 'white Africans', this is tempered by their use of the word 'African' to always and only to refer to blacks. As such, white farmers in Zimbabwe are 'orphans of empire', unable to progress past this state of being thus 'become' Zimbabwean".

In some ways the book could be critiqued as unbalanced. Pilossof found it difficult to gain access to information, and many people would not speak, so charged was the atmosphere in the mid 2000s. His interviews are with an extreme group – JAG – which many would say was not part of the mainstream, although it was plentifully supported by foreign donors. He also interviewed people in the heart of Mashonaland where the land invasions were most contested, and where violence was most prominent. Also, after 2000 The Farmer was in its dying days, when it was most shrill in its criticisms of the land reform, rejecting the more conciliatory stances of some within the CFU. He also uses the sometimes bizarre white memoirs and biographies as sources, which many would argue offer particularly odd interpretations of white Zimbabwe. He therefore did not speak to those realists and pragmatists who perhaps saw the land reform as the 'writing on the wall', something that was inevitable and that had to be accommodated. He did not discuss with those who did not have an escape route to town, with alternative non-farm businesses, and so did not speak to those who sought compromises and accommodations on their farms. And he did not speak to those few who actually supported land reform, even if not the form it took. This is another dimension of white farmers' voices that needs to be told, and awaits another book.

But such gaps do not undermine the value of the book, as the array of perspectives garnered while showing variation and lack of clear consensus, definitely shows a particular and well recognised discourse. As a documentation of the perhaps inevitable end of an era spawned by a brutal form of settler colonialism it provides a rather sad and telling doorstop to a troubled period.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Contested agronomy: low-level evidence, high-level claims

|

| Image: success rice, from nauright's photostream on Flickr |

Demonstrating 'impact' has become a strong imperative for those involved in agronomic research. An important part of the new dynamic of contestation about the outputs of agronomic research in the developing world arises from this imperative. That’s one of the themes of the book Contested Agronomy and in a recent paper.

Whether couched in terms of ‘success stories’, ‘value for money’ or ‘impact at scale’, this pressure is now a critical part of the context of agronomic research. It affects how it is prioritised, funded, managed, implemented, evaluated and communicated.

There is nothing new in agronomists and their institutions labelling emergent findings and technologies as ‘promising’ – or using these to attract public attention and make the case for further funding. However, there is something qualitatively different between a claim of ‘promise’ and a claim of future ‘success’ or ‘impact’.

‘Success making’ within agricultural research in the developing world, therefore, deserves further attention. What are the links between the data generated through agronomic experimentation, and claims of actual or potential ‘impact at scale’?

What happens when ‘impact’ takes over? An important part of the new dynamic of contestation about the outputs of agronomic research in the developing world arises from the imperative to demonstrate impact. That’s one of the themes of the book Contested Agronomy and in a recent paper. Whether couched in terms of ‘success stories’, ‘value for money’ or ‘impact at scale’, this pressure is now a critical part of the context of agronomic research. It affects how it is prioritised, funded, managed, implemented, evaluated and communicated.

There is nothing new or even noteworthy in agronomists and their institutions labelling emergent findings and technologies as ‘promising’ – or using these to and using labels such as this to garner attract public attention and make the case for further funding. However, we have previously suggested that[NO1] there is something qualitatively different between a claim of ‘promise’ and a claim of future ‘success’ or ‘impact’.,

The foundational level at which applied agronomists work is the trial plot. Whether these trial plots are located on experiment stations or in farmers’ fields, work at this level characterises much agronomic research. Relatively few agronomists work at the field and farm levels, often by combining an element of modelling with their experimental activities, and all too rarely by working in close collaboration with social scientists. Agronomists have a long tradition of using experimental design, and repeating similar experiments over different locations, seasons and years in order to make their findings more robust and to increase the level at which they can be applied.

The foundational level at which applied agronomists work is the trial plot. Whether these trial plots are located on experiment stations or in farmers’ fields, work at this level characterises much agronomic research. Relatively few agronomists work at the field and farm levels, often by combining an element of modelling with their experimental activities, and all too rarely by working in close collaboration with social scientists. Agronomists have a long tradition of using experimental design, and repeating similar experiments over different locations, seasons and years in order to make their findings more robust and to increase the level at which they can be applied.In contrast, in order to be taken seriously, a response to the pressure to demonstrate success and impact must be made at levels considerably higher than the trial plot, field or farm. A recent paper by Kassam and Brammer illustrates how claims for the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) and Conservation Agriculture (CA) are being made at these higher levels:

“...in the coming decades, both CA and SRI appear to offer the best hope of increasing food production rapidly, at low cost and without adverse environmental consequences in developing countries where human populations are increasing most rapidly. CA principles can strengthen the sustainability and productivity of most tillage systems (including ‘organic’ systems) in arable farming, horticulture, plantation agriculture, agro-forestry and integrated crop–livestock systems.”

Here, the claims about both CA and SRI are made at the level of “developing countries where human populations are increasing most rapidly”. For CA, they’re made at the level of “most tillage systems [...] in arable farming, horticulture, plantation agriculture, agro-forestry and integrated crop–livestock systems”.

These are high level claims by any stretch of the imagination; and Kassam and Brammer are not the only ones making them. The question that deserves our attention is: How are such claims constructed; and can (how can) they ever be refuted?

We might think of such a high level claim as being like a large brick edifice. One way of constructing it would be brick-by-brick, where each new brick represents an additional piece of evidence. In the case of agricultural technologies such as SRI and CA, this additional evidence might expand the array of soil types, rainfall regimes, production systems, and so on, in which these technologies have been shown to both yield significant benefits and be practicable.

A high level claim constructed in this way would arise from, and would link directly to, a base of experimental or observational data that could be made available to be re-interrogated as required.

However, high level claims of the potential impact or success of agricultural technologies are seldom constructed in this way - primarily because the additional experimentation would simply be too time consuming and expensive. Funders don’t want to pay for that intensity of research, and everyone is under pressure to demonstrate results quickly.

So, rather than building a claim to ‘impact at scale’ by adding one brick of evidence to another, what appears to happen is that a very limited quantity of site-specific data is ‘stretched’: this allows the creation of a large but paper thin edifice that, to the eye of someone who is ready to believe, appears solid and robust.

The problem is that once such a large-scale claim has been established, despite having little real substance, it can be extraordinarily resistant to attack on the basis of argument and evidence.

This is partly because of the level at which the claims are made. As such claims is are not rooted in the world of evidence and are made in such general and universal terms, any critique based on the low-level counter-evidence of the agronomist (i.e. from trial plots, fields and farms) is repelled like water off a duck’s back. Emery Roe has made a similar observation in relation to the staying power of some development narratives, despite the existence of a significant body of undermining evidence.

This situation, where impact claims are largely divorced from the experimental evidence that is the life-blood of applied agronomy, and where mainstream academic journals increasingly allow themselves to be part of the process of ‘stretching’, represents a fundamental challenge to the discipline.

How agronomists respond to this challenge will, to a large extent, determine their relevance to sustainable agricultural development over the coming decades. We very soon need to see the green shoots of an agronomy fight-back!

References

- Kassam, A., & Brammer, H. (2012). Combining sustainable agricultural production with economic and environmental benefits. The Geographical Journal, no-no. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4959.2012.00465.x

- Roe, E. M. (1991). Development narratives, or making the best of blueprint development. World Development, 19(4), 287-300.

- Sumberg, J., Irving, R., Adams, E., & Thompson, J. (2012). Success making and success stories: agronomic research in the spotlight. In J. Sumberg & J. Thompson (Eds.), Contested Agronomy: Agricultural Research in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

- Sumberg, J., & Thompson, J. (Eds.). (2012). Contested Agronomy: Agricultural Research in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

- Sumberg, J., Thompson, J., & Woodhouse, P. (2012). Why agronomy in the developing world has become contentious. Agriculture and Human Values, 1-13. doi: 10.1007/s10460-012-9376-8

STEPS Symposium 2013: S is for Society

Guest blog by Sandra Pointel, Doctoral researcher, SPRU

The last session of the STEPS Symposium on Credibility Across Cultures was promising. Its focus on "power, plurality and uncertainty" promised to shed light on how to open up expert advice, improve the governance of the science and technology decision-making process and engage with the wider public, all recurrent themes throughout the two day event.

The presence of some surprise participants - a group of students concerned with the current wave of privatisation and its impact on education - gave further resonance to speakers' calls for opening up expert advice and allow questions to be asked by all voices. Don't get me wrong: the debate was not about privatisation either at the University of Sussex or within the wider education system in the UK. But the participation of newcomers to the high-level discussions on scientific advice for sustainability offered an interesting curtain raiser to explore power and the role of social movements in widening a debate that has mainly taken place in closed circles of scientists and policy-makers.

When faced with uncertainty, power and plurality matters, Professor Andy Stirling, STEPS Centre co-director, reminded the audience.

Despite many efforts to strengthen scientific methods, social movements are key in making space for all these voices to be heard. Indeed, power does not necessarily lie with politicians. "Social movements play an important part, especially in the long view, as illustrated with the 1970's environmental movement which played a key part in changing the framing," said Susan Owens, Professor of Environment and Policy at the University of Cambridge.

Earlier in the day, Professor Lidia Brito, Director of Science Policy, at UNESCO, had emphasised that 'S' should stand for society rather than science. Connections between science and society are crucial if fruitful engagement with policy is to be achieved, she explained: "If scientists question a lot, society does it even better".

But governing S&T and ensuring that all voices are heard remains a sticky issue both within global structures for scientific advice such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and at national level. In the UK, for example, the quest for good governance of technoscience is not new, as Prof Owens pointed out. New and emerging technologies require scrutiny beyond technical assessments to gauge their social and environmental impacts. Concerns about the disposal of nuclear radioactive waste, health impacts of nanotechnology and, more recently, geoengineering and fracking, have all highlighted major governance issues.

While all these technologies have been subject to scrutiny, the persistence of concerns appears symptomatic of a debate that is often closed down. In the case of fracking, for example, critics remain virulent despite the Royal Society's conclusions that associated health, safety and environmental risks extraction can be managed effectively in the UK. "Where most people diverge is not necessarily on science," Susan Owens emphasised.

Indeed, deliberation in public, and public deliberation, have different takes on opening up. Key questions need to be asked to clearly identify who the process is being open to, what you engage with and at what stage the process is being open: all of which trigger different answers with very different models of public engagement.

Rather than narrowly focusing on risks, a key step is to encompass different views of both benefits and dangers and provide direction and application and control of technologies. Furthermore technology assessments and political processes must go in tandem to consider meaningful insights from new guests, including "uninvited participants", to avoid an expert/public divide.

Scrutiny about the role of money and power in constructing expertise and the potential impacts of the privatisation and corporatisation of science is also needed, said Dr Suman Sahai, the Delhi-based convenor of GeneCampaign. Already well-informed younger generations are questioning S&T because of the lack of transparency and participation of the decision process, she said.

All these of issues need to be tackled, and with some urgency, if credibility is to be maintained across and within cultures.

To view resources, video, commentary and slides from the event, visit the Symposium page on the STEPS Centre website.

|

| Susan Owens. Photo: Lance Bellers |

The presence of some surprise participants - a group of students concerned with the current wave of privatisation and its impact on education - gave further resonance to speakers' calls for opening up expert advice and allow questions to be asked by all voices. Don't get me wrong: the debate was not about privatisation either at the University of Sussex or within the wider education system in the UK. But the participation of newcomers to the high-level discussions on scientific advice for sustainability offered an interesting curtain raiser to explore power and the role of social movements in widening a debate that has mainly taken place in closed circles of scientists and policy-makers.

When faced with uncertainty, power and plurality matters, Professor Andy Stirling, STEPS Centre co-director, reminded the audience.

Despite many efforts to strengthen scientific methods, social movements are key in making space for all these voices to be heard. Indeed, power does not necessarily lie with politicians. "Social movements play an important part, especially in the long view, as illustrated with the 1970's environmental movement which played a key part in changing the framing," said Susan Owens, Professor of Environment and Policy at the University of Cambridge.

Earlier in the day, Professor Lidia Brito, Director of Science Policy, at UNESCO, had emphasised that 'S' should stand for society rather than science. Connections between science and society are crucial if fruitful engagement with policy is to be achieved, she explained: "If scientists question a lot, society does it even better".

But governing S&T and ensuring that all voices are heard remains a sticky issue both within global structures for scientific advice such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and at national level. In the UK, for example, the quest for good governance of technoscience is not new, as Prof Owens pointed out. New and emerging technologies require scrutiny beyond technical assessments to gauge their social and environmental impacts. Concerns about the disposal of nuclear radioactive waste, health impacts of nanotechnology and, more recently, geoengineering and fracking, have all highlighted major governance issues.

|

| fracking, labour party conf 2012 by manchesterfoe on Flickr (by-nc-sa) |

Indeed, deliberation in public, and public deliberation, have different takes on opening up. Key questions need to be asked to clearly identify who the process is being open to, what you engage with and at what stage the process is being open: all of which trigger different answers with very different models of public engagement.

Rather than narrowly focusing on risks, a key step is to encompass different views of both benefits and dangers and provide direction and application and control of technologies. Furthermore technology assessments and political processes must go in tandem to consider meaningful insights from new guests, including "uninvited participants", to avoid an expert/public divide.

Scrutiny about the role of money and power in constructing expertise and the potential impacts of the privatisation and corporatisation of science is also needed, said Dr Suman Sahai, the Delhi-based convenor of GeneCampaign. Already well-informed younger generations are questioning S&T because of the lack of transparency and participation of the decision process, she said.

All these of issues need to be tackled, and with some urgency, if credibility is to be maintained across and within cultures.

To view resources, video, commentary and slides from the event, visit the Symposium page on the STEPS Centre website.

Thursday, 21 February 2013

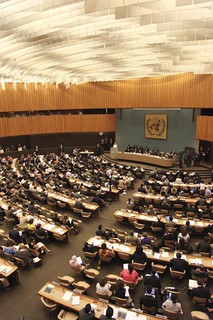

What role does the scientific community have in post-2015 debates?

|

| ECOSOC, from unisgeneva's photostream on Flickr |

Those who work in the development field currently find themselves in tricky debates around the future of the MDGs, the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Post-2015 framework as a whole. Having to deal with numerous disjointed and confusing processes, hundreds of meetings, and an astounding amount of information, it has been hard to dedicate enough time for proper reflection, analysis and planning.

Fortunately, the STEPS Centre Symposium helped to shed light on the role of science in this important moment for the future of development.

In the session Beyond Rio+20: improving global structures for scientific advice, Lidia Brito brought one clear message: instead of focusing only on final outcomes, it is necessary to give more value to influencing processes – in her own words, 'it is all about keeping the conversation going'. For the scientific community, the Rio+20 conference was far from a failure as it gave science an important space in the agenda. Now, the goal is to keep improving the spaces and mechanisms for scientific advice to policy-makers, seizing opportunities such as the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)'s focus on the role of science, technology and innovation in 2013, the new UN Science Advisory Board, and Future Earth.

Robert Watson added to this by stressing the importance of reconsidering the way science is communicated: to magnify impact in public policies, it is necessary to make clearer connections to issues that a broader audience can relate to, such as food, energy and water. Furthermore, Watson mentioned the need for a multi-disciplinary approach to science, and the urgency for closer interactions with local traditions and indigenous knowledge.In a second session related to the Post-2015, From MDGs to SDGs: aspirations, evidence and diversity in setting global goals, the panelists expanded the debate.

Camilla Toulmin highlighted several crucial factors that have been weakly addressed by the MDGs and must receive much higher attention in the Post-2015 framework: universality, inequality, accountability, integration between goals, mechanisms for implementation at national and local level, and long-term political leadership.

Duncan Green looked at things from a different perspective, and posed an important question: by focusing so much on analyses and consultations to try to find out which should be the next development goals, aren't we leaving aside a deeper reflection about the implementation side? Apart from countries highly dependent on aid, the MDGs didn't bring a notable impact on national and local policy-making – shouldn't we dedicate more attention to finding out how to change that?

Finally, Chris Whitty brought attention to the fact that the scientific community needs to look for three different types of evidence to influence the Post-2015 processes in a consistent way:

- evidence of need, to identify the real needs of the present and future generations;

- evidence of reasons for why the things are the way they are;

- and evidence of impact, that shows how change really happens on the field.

Although we all still have much more questions than answers, the STEPS Symposium surely helped clarifying the current state of the Post-2015 debates and the role science can play in the ongoing processes. The call for action is strong, and several spaces for engagement already exist.

Coming from Brazil, I would like to add two more questions to the list. It is clear to me that the scientific communities of many developing countries are much more distant from influencing development policy than those of the North. How can we use Post-2015 to change that? And which types of partnerships between institutions and individuals from the North and South can help in the process?

It looks like we have got a lot of work to do!

To view resources, video, commentary and slides from the event, visit the Symposium page on the STEPS Centre website.

This article was originally posted on the The Crossing.

Fear of flying: the uneasy marriage of numbers and risk

STEPS Centre co-director Prof Andy Stirling has written an article for the Guardian's new blog, Political Science, about how using numbers to communicate risk can create a false sense of certainty.

The new Guardian blog offers insights into the interaction of science and politics, with guest posts and regular contributions from Alice Bell, Kieron Flanagan, Jessica Bland, Mariana Mazzucato, Jack Stilgoe and James Wilsdon.

Andy Stirling: Fear of flying and the hazards of communicating risk (The Guardian, 14 February 2013)

This article was originally posted on the The Crossing.

New FHS-led webinar - Shaping the future of health markets

In the run up to the Private Sector in Health Symposium in July, the co-ordinators are organising a webinar series to highlight key issues and debates about the role of non-state actors in providing health services.

The first webinar was convened by the Center for Health Market Innovations and featured recent research from India on informal providers.

The Future Health Systems consortium is pleased to be convening the next webinar in the series, 'Shaping the future of health markets: Reflections from Bellagio'. The webinar will take place on 7 March 2013 at 07:30EST/12:30GMT/18:00IST and will be chaired by FHS CEO Dr Sara Bennett.

The webinar comes at a critical time, as the UN has recently adopted a resolution encouraging countries to work towards universal health coverage. Governments will have to strike a pragmatic balance in how they approach that task.

The webinar will first present landscaping reviews undertaken by members of the Future Health Systems consortium along three health market themes: regulation, networks, and learning. Key recommendations outlined in the Bellagio Statement on the Future of Health Markets will also be addressed. This will be followed by reactions from a variety of stakeholders -- from small business leaders, to private sector giants, health funders, and government representatives -- some of whom participated in the meeting in Bellagio.

For more information and to register to attend, visit the Private Sector in Health website.

Know your constituency: a challenge for all of Zimbabwe’s political parties

In the bad old days of one party rule, rural constituencies knew their place. They voted for the ruling party and in exchange they were offered the basics: some improvements in infrastructure, an education and health system that were an improvement on the past, and critically food in times of drought. There were exceptions of course – notably in Matabeleland in the 1980s when terrible vengeance was wrought on those deemed to be supporting 'dissidents'. But elsewhere, in exchange for compliance and consistent voting, a social and political contract was struck between the state (in essence the ruling party) and rural people. And, yes, when there was wavering, violence was meted out, as has always been the way with the party of the armed struggle, ZANU-PF.

This then was the post-independence deal which persisted until the emergence of the MDC in the late 1990s and a tangible opposition with clout (of course there were precursors, but these never changed much). Since then voting has been much more divisive. The constitutional referendum of 2000 put it all into sharp relief, and the parliamentary, presidential and senatorial election that followed presented a similar pattern. The MDC won the urban areas and ZANU-PF won the rural. Again there were variations, especially in Matabeleland and Manicaland, but ZANU-PF's pact with the rural populace stuck. Of course in 2008 it became more frayed, and the pattern of violence rose to new, more horrifying heights. But even then civil society recorded voting patterns show that largely the rural population continued to back ZANU-PF. Land reform of course helped, as did intimidation and violence, particularly in Mashonaland East, but the sense of loyalty, commitment and a recognition of strong leadership was apparent too.

As we and others have argued extensively, over the past dozen years land reform has radically reconfigured the rural landscape. New resettlement areas now make up nearly a quarter of the land area of the country, representing a population of 170,000 households, over a million people. Perhaps even more significant than this significant demographic and geographic shift, is the pattern of class-based differentiation that has resulted.

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Agrarian Change we argued that, due to the process of 'accumulation from below' by a significant proportion of new settlers who are producing surpluses and investing profits in rural areas, a new class of 'middle farmers' is evident. Perhaps 30-40% of the A1 farmers in our Masvingo sample sites could be classified in this group. They are entrepreneurial farmers, connected to increasingly sophisticated value chains and market outlets, selling crops and livestock regularly, hiring labour and investing in their farms. This group is most prevalent in the so-called A1 self-contained farms, where a farm block was allocated to individuals, in comparison to the villagised scheme where people are resident in villages and grazing areas are communal.

Such accumulators are also evident in the A2 farms. Fewer proportionately have made it, however, due to the challenges of finance and credit constraining their abilities to invest. But some have, and are doing well. Some of these include those who might be regarded as 'accumulating from above', deriving patronage from the state or political favours from the party. Even some of the 'cronies', it seems, are keen to accumulate from agriculture, perhaps knowing that their sources of patronage are likely to be short-lived.

In the past when accumulation through agriculture was available to only very few in the communal or old resettlement areas, as land areas were small, capital scarce and opportunities for market engagement constrained. Even in the boom time of communal area agriculture soon after Independence only around 20% of communal area farmers in the Highveld areas regularly sold maize to the market. This smaller group of communal area accumulators persist, and remain important in terms of overall production nationally, even if they are scattered across wide areas.

As Bill Kinsey and his team have shown over the years, in the old resettlement areas there were processes of differentiation similar to what we have observed in the new land reform areas. Some beneficiaries did indeed do well, producing surpluses and attracting others to their homesteads. But in terms of overall numbers the old resettlement areas were never going to make inroads into a broader political dynamic in the countryside. The same applied to the small-scale farming areas. These former Purchase Areas were established by the colonial regime to create a yeoman class of middle farmer, an attempt to buy off resistance to the regime, and provide a buffer to the large-scale commercial farming areas. This rural black elite had its own political trajectory, but it never really influenced national politics in any big way, beyond the impact of a few individuals.

So why is this new class dynamic unleashed by land reform potentially significant for Zimbabwean politics and the next election? An important factor is the sheer scale of numbers. A rough calculation done by Ben Cousins and myself for a forthcoming paper suggests that the new accumulators in new land reform areas amount to a substantial potential adult voting population. Add to these the accumulators in the communal areas, the old resettlement areas, the small-scale farming areas, and the remnants of the commercial farming sector, we are talking of about a million rural voters seriously reliant on and committed to accumulation through agriculture. This is perhaps around 18% of the total electorate, a quarter of rural voters: a significant number in any electoral calculation (although who is on the voters' roll is yet another debate).

Large numbers of people can of course be bought off or intimidated to vote, as has happened before. There are after all around three million potential voters in the communal areas, perhaps more (the 2011 census will tell all soon hopefully). However, this group of accumulating middle farmers are more vocal, educated and organised than the standard image of the rural electorate, especially in the new resettlement areas. All the studies done to date show how the land invaders were generally younger and better educated than their communal area counterparts. They are also better connected: to towns and markets, to the bureaucracy and to political leaders. This makes a difference in terms of negotiating social, political and economic space for their farming activities, but also in terms of lobbying, influencing and organising. While the new settlers are not formally organised, they are certainly engaged in a range of organisational activities, whether organising cotton buying or livestock trading at a local level.

Geography helps too. The rural areas are not in the same configuration spatially as they were before. A1 schemes abut communal areas which are connected to old resettlements and A2 areas. And everyone meets in new rural business centres, bus routes or market places in town. Because A1 areas were largely invaded from nearby communal areas and urban centres, people are connected socially too. They are friends, relatives, sharing churches, totems, ancestors and religious sites.

Any political party should take heed. This middle farmer group is potentially an important constituency. In the past, as Jeffrey Herbst and Angus Selby have shown, white farmers organised effectively and managed to capture the colonial state, bending policy after policy to their advantage. They were pretty effective after Independence too, striking important deals with the new government. Can the new accumulators, centred in the new resettlement areas, and particularly the A1 schemes, form such a politically strong group? It will of course be far more difficult, as they lack the collective economic muscle and financial backing for a strong farming union, but politically they may become significant if they can bring others with them. Would any government be able to resist the demands of such a group if they allied with the rest of the communal area population demanding attention for rural and farming issues?

A strong narrative about land, agriculture and economic development is an essential precursor. No political party offers this now. ZANU-PF resorts to its tired nationalist rhetoric, while the MDC formations seem unable to create a convincing rural policy position at all. There is a political opportunity here. Whoever can respond to the new politics of the Zimbabwean countryside will, I reckon, win substantial backing. Rural people can no longer be fobbed off with empty promises and a commitment to provide drought relief. As up and coming entrepreneurs committed to rural businesses, they want more: finance, investment, infrastructure and strong state backing. Let’s see if the political parties respond during 2013.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Thursday, 14 February 2013

STEPS Symposium 2013: Beyond Rio+20 - Improving global structures for scientific advice

|

| Lidia Brito. Photo: Lance Bellers |

In recent years, global initiatives have attempted to co-ordinate scientific advice and assessments – on climate change, biodiversity and agriculture, among other topics. The second day of the STEPS Symposium on the global politics of scientific advice opened with a panel looking at these global structures.

Prof Ian Scoones, co-director of the STEPS Centre, introduced the session by asking how assessments should be organised; who is included, who decides and what are the underlying politics?

The two panellists, Prof Lidia Brito, director of UNESCO's science policy division, and Prof Sir Robert Watson, former Chief Scientific Advisor for DEFRA, drew from their extensive experience to address the question of what makes for effective and successful international engagement between scientific advice and policy making.

The two presentations were very different in style, and presented different approaches to building effective structures for scientific advice. Prof Brito focused on the importance of ensuring that science and policy address societal needs, which, she said must be at the heart of any process. She stressed that processes should connect the three worlds of policy formation, scientific enquiry and societal need. In order to do this, openness and engagement were vital to "multiply faces and amplify voices". Scientific evidence should be embedded in all stages of a process, rather than just included at the end in advice to policy makers, she said.

Prof Brito also stressed that policy processes should include capacity building, as scientific capacity is not equally distributed. Countries are not equally able to participate in policy processes, reinforcing hidden power relations. Power dynamics also come into play when examining what issues are covered in the processes, whose questions are addressed, and what forms of knowledge are included as evidence.

|

| Bob Watson. Photo: Lance Bellers |

Prof Watson outlined the experiences and lessons learned from several processes, including IAASTD and IPCC; and discussed two processes still under development: IPBES (Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) and the Future Earth project.

He described the key factors for a successful process, highlighting the need for processes to be open and involve a balanced range of stakeholders who are able to work together to co-design and co-produce the outputs. Ownership and participation were vital, he said, as are evidence-based outputs, which can be peer-reviewed. Global assessment processes must be multi-disciplinary and focus on the needs of society, he said, stressing the importance of stakeholder engagement, co-production and trans-disciplinary working.

Questions from the floor focused on knowledge – whose, what sorts, and where international assessments look for knowledge; how power relations are taken into account when using knowledge from different communities; how 'expertise' is defined; capacity building; and the politics of knowledge production. A concern was raised that the questions of interest to communities at the grassroots may not be those being asked by international panels; how can these be incorporated but not subsumed into a single consensus?

There was a concern from one delegate that the talk of openness and participation can at times be nothing more than rhetoric. A nother raised the legitimacy of the 'indigenous' representatives participating in the processes: how are they selected and who does the selecting?

The session raised many questions about the value and purpose of global assessments, but did not, in my view, wholly manage to grapple with questions of power and politics in global deliberations. The perspectives of marginal communities in developing countries remained marginal to the discussion of assessing global linkages across multiple sectors.

Many of these questions are about how to include, and reflect, more views in global scientific processes. How can rhetoric about inclusiveness be turned into a real attempt to look at questions about what sort of expertise is included? Who are the participants in global processes? Are they just part of the international development juggernaut - the same people talking to each other in multiple fora? There was a call for policy solutions to address the needs of stakeholders, but who defines who the stakeholders are? The presentations demonstrated a huge ambition to link global issues, but how do they make an impact on people's daily lives?

If the theme of the session was how to design open and accountable decision-making processes and how they might use science effectively, the discussion raised many questions about whether these huge global assessment processes are open or accountable, who is involved in making the decisions, how the issues to be examined are chosen, how the questions are framed, what is considered to be scientific evidence, and much more.

The session raised more questions than it answered, but as Prof Brito had suggested that scientists should be interested in conflict stimulation – continually questioning evidence and understandings – perhaps that was appropriate.

To view resources, video, commentary and slides from the event, visit the Symposium page on the STEPS Centre website.

STEPS Symposium 2013: Science and developing countries - whose expertise counts?

|

| Dipak Gyawali at the symposium. Photo: Lance Bellers |

The second session of the STEPS Symposium on the global politics of scientific advice asked 'whose expertise counts?'

In his opening comments, Professor Brian Wynne (University of Lancaster) turned this question around by asking "whose questions count?" He described how sheep farmers in the UK asked relevant questions of scientific advisers and made observations following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (as discussed in his paper from 1992). Prof Wynne explained that in this context the questions and observations from farmers were largely ignored by scientists.

This analogy made me think of farmers in a very different, developing-world context. Small-holder farmers in developing countries frequently have few channels through which they can question, critique, or respond to science or policy. In these contexts, policy is prescriptive. While some participatory development projects aim to involve local communities in identifying issues and determining policy, cases where this is being successfully implemented are far outnumbered by cases where there is no such project.

The issues surrounding local, indigenous expertise in a developing country context were only briefly raised during this session. Dr Dipak Gyawali (Nepal Academy of Science and Technology) spoke about the need for more 'toad eye' science and less 'eagle eye' science (his slides are here). Though this acknowledges that scientific expertise can come from places outside of academia, his discussion did not elaborate on the challenges this presents to hierarchies and how academia and the policy arena can engage with this.

Dr Alice Bell (SPRU, University of Sussex) spoke about the role of the public as experts in a developed world context. She suggested that social media tools such as Twitter can act as a tool to mobilise the public in challenging scientific advice (see also her earlier post on this blog). During her presentation (slides here) my thoughts again turned to how this may be reflected in a developing country context where access to social media is less widely available, especially in rural areas. For example, could local radio, widely used throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, could play a role in the vocalisation of public opinion regarding science and policy debates?

Policy and science in developing countries often come from, or are heavily influenced by developed countries, especially those with colonial links. It is worth considering whether it is harder for developing countries to critique or dispute science from developed countries, or to question the 'authority' assigned to scientists in developed countries.

Later in the day, in her keynote lecture, Anne Glover (Chief Scientific Adviser to the President, European Commission) used the example of genetically modified (GM) crops to illustrate this problem. She explained that if European countries refuse to use GM crops, developing countries would also refuse them (slides here). This example highlights the influence of hierarchies from north to south. In the case of GM crops, developing countries have the potential to benefit most from growing them, according to Prof Glover, and they are often cited as a 'fix' for increasing food production in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is for reasons such as these that those engaged with development, science and policy arenas must challenge hierarchies of authority, expertise and influence.

Discussions around authority of expertise and whose expertise counts centred on UK and western science and policy systems, and not those of developing countries. Where the context and systems are so different, understanding whose expertise and questions count is a complex issue: but it's arguably a more important challenge because of population and economic growth in developing countries. To me, surrounded by such eminent academics, these issues were under-addressed throughout this session.

Though questions regarding 'whose expertise counts?' in a developing country context was under-represented in this session, they were referred to. Issues regarding 'whose questions count', however, as raised in the opening remarks of the session, were not touched on. In sessions the following day, Professor Lidia Brito (UNESCO) and Dr Camilla Toulmin (International Institute for Environment and Development) both referred to 'who is asking the questions?' Throughout all of the Symposium's five sessions, however, no one attempted to adequately respond to this.

To view resources, video, commentary and slides from the event, visit the Symposium page on the STEPS Centre website.

Anne Glover on science advice in Europe

The STEPS Centre's symposium on the global politics of science advice looked at how evidence informs decision-making. The speakers included Prof Anne Glover, Chief Scientific Adviser to the President, European Commission, who gave a public keynote lecture at the end of day 1.

Under the title "What is the right balance between respecting evidence and living in the real world?", she spoke about how scientific advice structures operate in the EU.

Here's the video of her lecture, which included questions from the audience:

You can also view Prof Glover's slides, as well as those of the other speakers, on the STEPS Centre website.

Under the title "What is the right balance between respecting evidence and living in the real world?", she spoke about how scientific advice structures operate in the EU.

Here's the video of her lecture, which included questions from the audience:

You can also view Prof Glover's slides, as well as those of the other speakers, on the STEPS Centre website.

Monday, 11 February 2013

Land Reform in Zimbabwe Revisited: Reflections from a book launch in London

by Ian Scoones and Dr Admos Chimhowu

At the end of January, the influential London-based think tank, Chatham House, hosted the launch of a new book on Zimbabwe's land reform – Zimbabwe Takes Back Its Land. It generated some UK media coverage which in turn provoked an outcry from some activists based in London, the Zimbabwe Vigil. Outside Chatham House, they organised a small protest, and handed out leaflets with commentaries from Ben Freeth, Eddie Cross (MDC Policy Coordinator General) and Charles Taffs (President Zimbabwe Commercial Farmers Union).

Why is it that the debate about Zimbabwe's land reform continues to generate such heat, perhaps especially in London? Why was it that a protest (admittedly in the end of only a few people) was organised about a book reporting empirical research? Why is it that those who oppose the land reform cannot engage with the empirical data? Why, after so long, can the debate not move on?

I was unable to attend the launch or interact with the protest and find out what they objected to, but I asked Dr Admos Chimhowu, a Zimbabwean scholar working at the University of Manchester, who was offering some comments at the event, to provide a report for this blog which he kindly did. Here are Admos' reflections:

"Fast Track Land Reform is fast becoming an interesting area of intellectual and policy exchange as more empirical evidence of its outcomes emerges. The most recent event aptly titled Land Reform in Zimbabwe Revisited: A Qualified Success? took place at Chatham House on the 31st of January 2013. The event focused on the evidence emerging from a recently published book, Zimbabwe Takes Back its Land (Kumarian Press) written by Joe Hanlon, Teresa Smart and Jeanette Manjengwa.

Even on a cold winter evening in London the event had all the elements of intrigue that have come to be associated with the Fast Track Land Reform (FTLR) in Zimbabwe. There was a capacity audience, a highly polarised debate and even a small, spirited but peaceful protest mounted by Zim Vigil outside.

Sir Malcom Rifkind MP was the discussant. Many may not know that Sir Malcom lived and worked in the Rhodesia in the late 1960s and wrote a very insightful MSc thesis on the Politics of Land in then Rhodesia in the 1960s. His views on the book were very carefully calibrated- recognising the rich historical analysis and the candidly presented empirical evidence. He focused on his own recollection of the polarised discourse in the Rhodesia parliament in the 1960s and also reflected on the post-independence dynamics. Addressing directly the now infamous 5th November 1997 Clare Short letter (about the British Government not taking responsibility to fund land reforms), Sir Malcom maintained the official UK government line that this should not be a British responsibility but one for Zimbabwe to prioritise.

Teresa Smart and Jeanette Manjengwa gave insights into the key findings of the book, arguing that notwithstanding all the criticisms of Fast Track, there is evidence that many smallholders who got land are using it to better themselves. Much of the discussion on the new book focused on its findings and it was clear that the polarisation that has characterised the land reform discourse continues. Some of the early evidence soon after 2000 pointed to a decline in production and productivity but more recent findings are showing a need to relook at what is happening on the land.

The publication in 2010 of Zimbabwe’s Land Reform: Myths and Realities marked a turning point in what has become a highly polarised discourse on the FTLR in Zimbabwe. This book was not only a marker of a new counter-narrative, seeking to challenge a generally accepted view that Fast Track Land Reform had been an unmitigated disaster, but it also sought to introduce some academic rigour into what had become a politicised lay and professional media discourse.

Adding new evidence, Zimbabwe Takes Back its Land supports this new narrative. It argues that FTLR in Zimbabwe has worked well for some, but could work better for more people with additional support. There is evidence of beneficiaries investing in and using land to improve their lives. This should not have been a surprise, because we know from past experiences of self resettlement that eventually people use the land to better themselves with or without state or other support.

At the Chatham House meeting there was a wide-ranging discussion, including on how the FTLR empowered women; lessons from Zimbabwe for South Africa; the need for support services for the beneficiaries; the need for more analysis of those who lost out; issues of employment and labour on the FTLR farms and patterns of emerging social differentiation on the farms. Others raised the contradictions between FTLR as being a success in tobacco production, while the country is still appealing for food aid. There were also challenges from the Commercial Farmers Union representatives who had flown in for the meeting on some of the figures used in the book. Even on a cold evening, Zimbabwe's land reform still produces some heat.

As evidence accumulates that the FTLR was not an unmitigated disaster, there are, in my view, some new dilemmas to address. There are:

The more I look at the evidence, the more I think we should actually not be surprised that asset transfer programmes will work in the medium to long term. This of course is a very separate question from the methods used to redistribute the land. How well asset transfers work of course will depend on a lot of factors and the book presents stories show cases of why institutional support, recapitalisation, skill and individual drive all matter."

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

At the end of January, the influential London-based think tank, Chatham House, hosted the launch of a new book on Zimbabwe's land reform – Zimbabwe Takes Back Its Land. It generated some UK media coverage which in turn provoked an outcry from some activists based in London, the Zimbabwe Vigil. Outside Chatham House, they organised a small protest, and handed out leaflets with commentaries from Ben Freeth, Eddie Cross (MDC Policy Coordinator General) and Charles Taffs (President Zimbabwe Commercial Farmers Union).

Why is it that the debate about Zimbabwe's land reform continues to generate such heat, perhaps especially in London? Why was it that a protest (admittedly in the end of only a few people) was organised about a book reporting empirical research? Why is it that those who oppose the land reform cannot engage with the empirical data? Why, after so long, can the debate not move on?

I was unable to attend the launch or interact with the protest and find out what they objected to, but I asked Dr Admos Chimhowu, a Zimbabwean scholar working at the University of Manchester, who was offering some comments at the event, to provide a report for this blog which he kindly did. Here are Admos' reflections:

"Fast Track Land Reform is fast becoming an interesting area of intellectual and policy exchange as more empirical evidence of its outcomes emerges. The most recent event aptly titled Land Reform in Zimbabwe Revisited: A Qualified Success? took place at Chatham House on the 31st of January 2013. The event focused on the evidence emerging from a recently published book, Zimbabwe Takes Back its Land (Kumarian Press) written by Joe Hanlon, Teresa Smart and Jeanette Manjengwa.

Even on a cold winter evening in London the event had all the elements of intrigue that have come to be associated with the Fast Track Land Reform (FTLR) in Zimbabwe. There was a capacity audience, a highly polarised debate and even a small, spirited but peaceful protest mounted by Zim Vigil outside.

Sir Malcom Rifkind MP was the discussant. Many may not know that Sir Malcom lived and worked in the Rhodesia in the late 1960s and wrote a very insightful MSc thesis on the Politics of Land in then Rhodesia in the 1960s. His views on the book were very carefully calibrated- recognising the rich historical analysis and the candidly presented empirical evidence. He focused on his own recollection of the polarised discourse in the Rhodesia parliament in the 1960s and also reflected on the post-independence dynamics. Addressing directly the now infamous 5th November 1997 Clare Short letter (about the British Government not taking responsibility to fund land reforms), Sir Malcom maintained the official UK government line that this should not be a British responsibility but one for Zimbabwe to prioritise.

Teresa Smart and Jeanette Manjengwa gave insights into the key findings of the book, arguing that notwithstanding all the criticisms of Fast Track, there is evidence that many smallholders who got land are using it to better themselves. Much of the discussion on the new book focused on its findings and it was clear that the polarisation that has characterised the land reform discourse continues. Some of the early evidence soon after 2000 pointed to a decline in production and productivity but more recent findings are showing a need to relook at what is happening on the land.

The publication in 2010 of Zimbabwe’s Land Reform: Myths and Realities marked a turning point in what has become a highly polarised discourse on the FTLR in Zimbabwe. This book was not only a marker of a new counter-narrative, seeking to challenge a generally accepted view that Fast Track Land Reform had been an unmitigated disaster, but it also sought to introduce some academic rigour into what had become a politicised lay and professional media discourse.

Adding new evidence, Zimbabwe Takes Back its Land supports this new narrative. It argues that FTLR in Zimbabwe has worked well for some, but could work better for more people with additional support. There is evidence of beneficiaries investing in and using land to improve their lives. This should not have been a surprise, because we know from past experiences of self resettlement that eventually people use the land to better themselves with or without state or other support.

At the Chatham House meeting there was a wide-ranging discussion, including on how the FTLR empowered women; lessons from Zimbabwe for South Africa; the need for support services for the beneficiaries; the need for more analysis of those who lost out; issues of employment and labour on the FTLR farms and patterns of emerging social differentiation on the farms. Others raised the contradictions between FTLR as being a success in tobacco production, while the country is still appealing for food aid. There were also challenges from the Commercial Farmers Union representatives who had flown in for the meeting on some of the figures used in the book. Even on a cold evening, Zimbabwe's land reform still produces some heat.

As evidence accumulates that the FTLR was not an unmitigated disaster, there are, in my view, some new dilemmas to address. There are:

- How can key actors begin to recognise and accept this growing body of evidence without being seen to endorse the methods used to achieve asset transfer? With South Africa facing similar challenges, any suggestion that massive dispossession undertaken at speed can produce good results in the long term would create problems for some interest groups. But then is dismissing FTL as an unmitigated disaster still tenable in the face of growing and credible evidence? We know that land reform can work to create the basis for long-term development (e.g. from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China), but what conditions need to be put in place now?

- If it is accepted that the FTLR has worked to improve some (not all) people's lives should it therefore not be accepted and supported (with all its history and faults)? This is particularly important for donors whose next question would be how to engage with the beneficiaries without being seen as endorsing the process through which these outcomes were achieved Indeed Sir Malcom Rifkind was very clear about his disdain for the methods of Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe. It seems to me that this dilemma can be resolved if the legal issues that remain unresolved are addressed- especially the issue of compensation. This is for the GoZ to work through and can potentially unlock further support for the FTLR beneficiaries.

- With elections looming in Zimbabwe the various political groups also have a crucial dilemma. Accepting that FTLR has worked for some and is beginning to yield results hands over political advantage to those who led or allowed this to happen. Rejecting the evidence though begins to sound insincere. It seems to me that this one will only be resolved after the elections!

The more I look at the evidence, the more I think we should actually not be surprised that asset transfer programmes will work in the medium to long term. This of course is a very separate question from the methods used to redistribute the land. How well asset transfers work of course will depend on a lot of factors and the book presents stories show cases of why institutional support, recapitalisation, skill and individual drive all matter."

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Thursday, 7 February 2013

Lessons from Thailand? A new rural economy and Zimbabwe’s political peasants

I have just been reading a fascinating book about rural Thailand called "Thailand's Political Peasants: Power and the Modern Rural Economy" by Andrew Walker from ANU. What on earth has this got to do with Zimbabwe, you ask?

Currently, a number of scholars are interested in the experience of southeast Asian countries in agricultural and rural development, and the lessons there may be for Africa, including an interesting research study looking at paired African-SE Asian comparisons. Such countries – including Thailand, but also Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia and Vietnam – have seen rapid economic growth overall, driven in part by a strong agricultural sector. The result has been plummeting poverty levels, and rising prosperity including in previously extremely poor rural areas. Their agricultural sectors have benefited from sustained state investment, including substantial input subsidies, strategic infrastructure development and reduced taxation. Land and tenure reform has been part of the story too, as more equitable land holdings provided a strong foundation for growth. There has of course been differentiation, and this has created a new class of rural dweller: someone who farms successfully, often linked into quite specialised value chains, but also someone who has also diversified into a range of off-farm activities, creating vibrant rural economies with strong forward and backward linkages. There are those who have dropped out too, but growing economies means potentials for absorption in gainful urban employment – or increasing rural employment as previously depressed rural areas boom.

In each of these countries, there has been a different pattern, phasing and geographically specific set of impacts. Thailand's Political Peasants focuses on the fortunes of northeast Thailand. Andrew Walker describes how

"Thailand's 21st century peasants have mobilised to defend the direct relationship they have established with the Thai state over the past 40 years. This is not the old-style politics of the rural poor, characterised by rebellion, revolution or resistance. Contemporary rural politics is driven by a middle-income peasantry with a thoroughly modern political logic. Their strategy is to engage with sources of power, not to oppose them".

Unlike other studies which focus on the economic factors, this book highlights the politics. The strong backing of Thaksin Shinawatra, often through highly corrupt, patronage arrangements, was an important factor. The rural population benefited from such investment, and backed Shinawatra and his party (and since 2011 by Yingluck Shinawatra). In the regular tussle between the urban based elite monarchists, the orange shirts, and the rural based red shirts, the national political dynamic is laid bare. But rural constituencies matter when they are doing well, and no political party in Thailand can ignore them, no matter how much the urban, industrial boom continues.

As discussed in an earlier blog, rural differentiation unleashed by land reform in Zimbabwe presents a new, and potentially powerful, constituency, reconfiguring the national political landscape. The emergence of a strong, vocal, relatively economically successful middle farmer group is an important new political phenomenon. Here the parallel with Thailand ends, however. Agriculture and rural development has not received the backing by the state, or any political formation, in the same way, and as a result the type of upward spiral economic growth seen in Thailand has not emerged. Zimbabwe's economy is severely depressed so non-rural alternatives are not available, and the middle income country dynamic seems a way off yet.

But perhaps, just perhaps, there are more lessons. They are all big ifs right now, but what if a new political settlement centred on this new rural constituency, and political survival and rural economic growth became intimately linked? What if the new windfalls from mineral resources were invested in rural revitalisation? What if this resulted in the sort of agriculture-led economic growth that we have seen hints of already, with spin-offs into employment, rural markets and the growth of rural towns? It will require a new political settlement combined with a new economic vision, neither of which are anywhere evident right now, but just maybe a shift in political forces in the coming years, driven by changes in class affiliations, motivations and alliances, will result in such a shift. In the 1970s, as Andrew Walker documents, no-one believed it would happen in Thailand; maybe in 20 or 30 years time Zimbabwe will look very different too.

This post was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland

Tuesday, 5 February 2013

From MDGs to SDGs: aspirations, evidence and diversity in setting global goals

By Adrian Ely, STEPS Centre Head of Impact and Engagement

This week's STEPS Centre Annual Symposium will be looking at the tensions between scientific advice and policy-making across international borders. I'll be chairing a session on the Thursday morning that will hear the views of leading development experts on the role of aspirations, evidence and diversity in the post-2015 international development agenda.

A couple of weeks ago, the uses of evidence in development decision-making were debated in a great set of posts on Oxfam's blog 'From Poverty to Power', written and maintained by Duncan Green. My colleague Nathan Oxley gave an overview of the debate in a blogpost last week . To some extent looking through the other end of the telescope, Thursday's session will be about how political aspirations can be turned into measurable goals and targets (upon which evidence can later be built). Defining the directions of development that we desire (what Jeff Sachs recently called "writing the future") will be a complex interplay between technical and political considerations.

The Millennium Development Goals were crafted over years of debate amongst a relatively small number of (primarily donor) actors around the OECD's development assistance committee (DAC). The DAC's 1996 report 'Shaping the 21st Century' proclaimed "we believe that a few specific goals will help to clarify the vision of a higher quality of life for all people, and will provide guideposts against which progress toward that vision can be measured." As a baseline for donors to focus their efforts and measure their impacts, the resulting goals have played an important role.

The post-2015 international development framework, including discussions around 'Sustainable Development Goals' is already involving a far larger and more diverse range of actors and interests than its predecessor. Participation in goal-setting is being emphasised and welcomed as part of United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon's high level panel of eminent persons (co-chaired by David Cameron). The Participate initiative co-ordinated by colleagues at IDS and Beyond2015 and the MyWorld survey are just two approaches that are opening up this process in very different ways. The Overseas Development Institute is now tracking proposed goals. The ONE campaign is running an SMS-based exercise in Southern Africa, and in a recent report argued that the outputs of this and other ground-level initiatives should be included in the High Level Panel's report.

The UN Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals that was set up following Rio+20 comprises 30 members (countries across the world including traditional 'donors', emerging economies and some of the poorest). In his initial input to this group, Ban Ki Moon wrote "overall, the SDGs should seek to envision a more holistic and integrated agenda for advancing human well-being that is equitable across individuals, populations and generations; and that achieves universal human development while respecting the Earth's ecosystems and critical life support systems. Strengthening the interface between science and policy can contribute to defining one set of appropriate goals, targets and indicators of the post-2015 development agenda."